By Wah Keung Chan

[Pour la version française, cliquez ici]

Conducting a great orchestra is like driving a Mercedes,” said the 42-year-old Keri-Lynn Wilson, the most prominent Canadian female conductor today. “When you get behind the wheel, it just feels right.” Wilson’s path from orchestra member to conductor came by chance. “I was just watching the Juilliard conducting class, and somebody asked me: ‘Oh, are you going to audition to conduct at Juilliard?’ I said, ‘No, no, no, I’m just watching’,’’ she related. That night, Wilson thought “What a great idea!” She prepared for the next 6 months and passed the audition.

Preparing for the audition meant lots of studying. There are written exams in music history and theory, every instrument, and every composer and their repertoire. There are also practical exams like reducing a score on the piano, sight-reading and ear training. A select few then get to conduct the Juilliard orchestra for a final test to narrow hundreds of applicants to two. That first time in front of her colleagues, Wilson conducted The Rite of Spring and Beethoven’s Symphony No 8. “I was nervous, but not nervous enough. Any conductor has a lot of courage. There’s something in you that is strong, that comes from preparation and knowledge. If you know a score, you’re that much more prepared. But what is unfamiliar to the young conductor are the gestures, the physical interpretation. Mentally you might have it, but it has to come out physically,” she remarked.

It wasn’t really a Cinderella story. Wilson explained, “I had had 12 years of sitting under the nose of a conductor in the orchestra; that’s a lot of knowledge already, watching and absorbing different styles.” Her passion for music started when she was three. Growing up in a musical family (her father was a violin teacher and the conductor of the Winnipeg Youth Orchestra), Wilson studied piano with her grandmother and “a bit of singing”, unsuccessfully, with her grandfather, before starting the violin with her father and eventually taking up the flute. Music was constantly heard in the house, and for Wilson, who was obsessed with music, it was a blessing. “Music was a part of my entire being and I couldn’t live without it,” she said.

Wilson kept up all three instruments throughout high school, and she was influenced by her uncle, cellist Eric Wilson, a star student of Leonard Rose’s at Juilliard. “I wanted to be just like him; going to Juilliard was the coolest thing,” said Wilson. At age 13, she studied for two weeks at Juilliard with flutist Julius Baker, who gave her encouragement. When she went back to audition for Juilliard for university studies, Baker remembered her and she was accepted.

Wilson’s first five years at Juilliard were packed. “I played under great conductors and I just loved the orchestral life of the musician. I loved the sound of the orchestra. Above all, the orchestral repertoire for a flutist is much more interesting than anything you can do as a soloist. I loved the Mahler, Brahms and Beethoven symphonies,” she explained. In her last year, Wilson slowly veered away from the flute: there were courses in Wagner and Verdi operas, and she accompanied singers on the piano.

The way Wilson dealt with her first feelings of nerves in front of the Juilliard orchestra has served the maestra well every time she meets a new orchestra. “What’s familiar is the unfamiliar. It makes the first encounter with a new group always exciting; there’s a bit of the unknown. I feel a little anxious; if you’re afraid, you’re in the wrong profession. In the first two minutes of music making, they are judging you on your musicianship. It’s an art that we’re doing and so there should be no reason why women can’t do it as well as men. It’s just something that’s coming from knowledge and emotional communication,” she said.

Wilson thrives on bringing that knowledge to her work. Her four years studying conducting taught her to analyse and study an orchestral score thoroughly. “When I started conducting I spoke two languages, and now I speak five. Now I know so much more about the composers, their lives—I’ve studied historically what’s going on. And doing a lot of operas, I can say I’ve read all the Pushkin, I’ve read all the Dostoevsky, everything that the operas stemmed from. It’s so important to just have all that knowledge,” she stated.

At Juilliard, Wilson studied with Otto Werner Mueller. She also spent a summer in Europe watching the maestros, including Claudio Abbado, work. Wilson observed that the German style is very clear and everything that you do connects exactly with the music. There is no sort of frivolous or extraneous movements that wouldn’t be exactly what the music indicated. “The Abbado [Italian] approach is much more fluid and spontaneous in his gestures. I think if you put together the German and Italian Schools, it makes for an interesting combination,” she said. “I like to be very clear and expressive. Everything I do physically is directly connected to your heart and mind.” There is also something quite Canadian in her conducting approach, which is based on diplomacy. “I like to make music together,” said Wilson. “I don’t like to dictate. I like to praise, and criticize during encouragement.” Being a woman, Wilson claims, has nothing to do with it. Wilson is adamant, “It’s 100% based on personality, even women can be tyrants.”

When Wilson talks about her favourite repertoire, the list of Shostakovich, Mahler, Brahms, Beethoven, Tchaikovsky, Mozart, Puccini, Verdi, Wagner, Strauss, shows that she a big romantic at heart. “I’m more extroverted and expressive.” Naturally, Wilson is equally at home in opera as the symphonic rep. When we spoke, she was studying Tchaikovsky’s Pique Dame for the first time as a replacement for Tel Aviv Opera in June.

“Before I even open the score of course I read Pushkin’s story, both in English and in Russian. Then I’ll see what Tchaikovsky was trying in his life; then you open the music and I’ll go through the entire libretto and know every word and its meaning. I do speak Russian, but at the same time there are words that I might not know so I sit with my best friend who is Russian. And then I markup my score, I do my analysis, and then put the words and the notes together and see what Tchaikovsky was looking for. Then I study it constantly so it becomes a part of your blood. Hopefully when it comes time to the first rehearsal I’ll know it cold.” Wilson also finds it important to listen to old and new recordings, especially operas to be aware of the traditions “because the breathing, cadenzas or flourishes are not necessarily in the score.”

Simon Boccanegra and Verdi

As part of the Montreal Opera’s 30th season, Wilson will conduct Verdi’s Simon Boccanegra, a story set in 14th Century Genoa, Italy, about the rise and fall of the city’s chief magistrate. “I love Verdi, especially late Verdi,” Wilson said. “It’s an opera that’s not done very much because of its convoluted, ridiculous storyline, and it doesn’t have the show-stopping tunes you’ll find in La Traviata or Rigoletto.” Verdi started writing Boccanegra in his middle period but revised it in his later period. “We think of Verdi’s operas and he pretty much follows the formula handed down from the Bellini-style operas with stop and go points where we all get up on our feet and applaud. But then we have Boccanegra and Otello, where he avoided this stopping. It’s more through-composed; he would write orchestral interludes [between scenes] instead. It was just much more continual music, which dramatically is stronger. There is rarely applause stopping the action, because he uses the carpet of the orchestra underneath these dramatic, transition moments. It’s much more Wagnerian in that sense.

When Wilson talks about the high points of the opera, you feel her enthusiasm. “For the audience it’s probably the finale of Act 1 where you have the entire chorus at its fullest, the orchestra is playing up a storm and then it comes to a halt with Boccanegra’s big concertate aria. From the slow movement, you go into a fast, virtuosic ending and it’s fun to conduct. I love the last act when Boccanegra is dying, Fiesco tries to comfort him and they reach peace together in a gorgeous duet, which is extraordinary for the darkness and its very rich harmonic colours. The way it ends is also very beautiful, and unoperatically quiet.” Wilson is also drawn to Boccanegra’s character, “He is a dream for a singer because he has so many different things going on emotionally in his life—his affections for his daughter, his devotion to his country, his hatred and all the things that come up in his life that make him a very complex and extraordinary figure.”

Wilson’s schedule shows lots of guest conducting appearances in operas and symphonies around the globe. Right now she’s happy with not having an orchestra of her own as she hasn’t had the right offer from the right orchestra that fits her personal life, as her marriage to Metropolitan Opera General Manager Peter Gelb keeps her hub in New York. You wouldn’t find a website for the maestra because she likes to keep her personal life private. “I’m in a profession where you can’t have any inhibitions when it comes to being very expressive in communicating the emotion in music. At the same time, I would rather read a book with candlelight.”

UPCOMING:

› ‑VERDI: SIMON BOCCANEGRA, Montreal Opera

March 13, 17, 20, 22, 25, 2010

operademontreal.com

› ‑SHOSTAKOVICH: SYMPHONY NO. 5, Orchestre Métropolitain

Jan. 27, 29, 30, 31, 2011

orchestremetropolitain.comLabels: Keri-Lynn Wilson

Last week, at the Long Center for the Performing Arts, Peter Bay and the Austin Symphony presented an all-Russian program: Rachmaninov’s Vocalise, followed by the Rachmaninov Piano Concerto No. 3, and closing with the Shostakovich Symphony No. 5, the Russian composer’s most popular symphony.

Last week, at the Long Center for the Performing Arts, Peter Bay and the Austin Symphony presented an all-Russian program: Rachmaninov’s Vocalise, followed by the Rachmaninov Piano Concerto No. 3, and closing with the Shostakovich Symphony No. 5, the Russian composer’s most popular symphony. The Rachmaninov Third Piano Concerto (Rach 3), performed on this occasion by soloist Barbara Nissman (photo: right), has become a calling card for piano virtuosi or would-be virtuosi from the days of one of the greatest, Vladimir Horowitz. It is a concerto guaranteed to bring down the house with its generous number of good tunes, its fearsome technical demands and its big finish.

The Rachmaninov Third Piano Concerto (Rach 3), performed on this occasion by soloist Barbara Nissman (photo: right), has become a calling card for piano virtuosi or would-be virtuosi from the days of one of the greatest, Vladimir Horowitz. It is a concerto guaranteed to bring down the house with its generous number of good tunes, its fearsome technical demands and its big finish. Nissman first met Argentinian composer Alberto Ginastera (photo: right) when she was a student at the University of Michigan. She went on to become one of his foremost interpreters and his Piano Sonata No. 3 Op. 55 is dedicated to her.

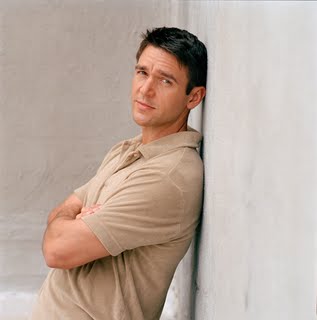

Nissman first met Argentinian composer Alberto Ginastera (photo: right) when she was a student at the University of Michigan. She went on to become one of his foremost interpreters and his Piano Sonata No. 3 Op. 55 is dedicated to her. Baritone Nathan Gunn (Photo: Dario Acosta)

Baritone Nathan Gunn (Photo: Dario Acosta)