Rach 3 Rocks with Nissman and the Austin Symphony!

Last week, at the Long Center for the Performing Arts, Peter Bay and the Austin Symphony presented an all-Russian program: Rachmaninov’s Vocalise, followed by the Rachmaninov Piano Concerto No. 3, and closing with the Shostakovich Symphony No. 5, the Russian composer’s most popular symphony.

Last week, at the Long Center for the Performing Arts, Peter Bay and the Austin Symphony presented an all-Russian program: Rachmaninov’s Vocalise, followed by the Rachmaninov Piano Concerto No. 3, and closing with the Shostakovich Symphony No. 5, the Russian composer’s most popular symphony.In the opening piece, Vocalise, Bay went for a nuanced, understated beauty that suited this slight work very well. Personally, I would like to hear more expansive phrasing in some sections, but then I may be biased by my own current research on that most rhapsodic of conductors, Leopold Stokowski.

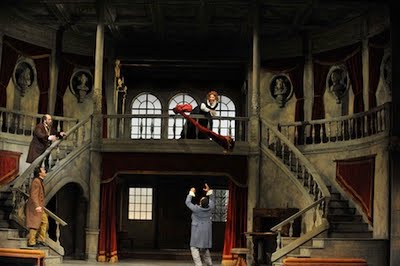

The Rachmaninov Third Piano Concerto (Rach 3), performed on this occasion by soloist Barbara Nissman (photo: right), has become a calling card for piano virtuosi or would-be virtuosi from the days of one of the greatest, Vladimir Horowitz. It is a concerto guaranteed to bring down the house with its generous number of good tunes, its fearsome technical demands and its big finish.

The Rachmaninov Third Piano Concerto (Rach 3), performed on this occasion by soloist Barbara Nissman (photo: right), has become a calling card for piano virtuosi or would-be virtuosi from the days of one of the greatest, Vladimir Horowitz. It is a concerto guaranteed to bring down the house with its generous number of good tunes, its fearsome technical demands and its big finish.But over the years we have learned that, while crucial, impeccable technique is not nearly sufficient for success with this piece. Finally, with Nissman, we got a performance that went deeper and illuminated more of the composer’s vision than any I have heard in a long time.

In Rach 3, many soloists settle for merely playing the notes accurately, in itself a formidable challenge. The great ones go further, as did Nissman, to make the music fresh and original, leaving listeners with a sense of having heard it for the first time.

In Nissman’s performance, this was especially true of the playful sections. Yes, the famously “sourpuss” Sergei Rachmaninov did indeed have a playful side. True, he wrote dark pieces such as The Isle of the Dead, but he wasn’t always morbidly depressed.

The third movement of Rach 3 has a scherzando section; it is here that we discern whether pianists are interpretive artists or merely technicians. Nissman played this section as it was surely meant to be played, in an improvisatory fashion, capturing all the sparkle and fun. It is not ‘Marx Brothers funny’ but it is witty and light-hearted. To capture the true spirit of this section is to add another dimension altogether to this great work, and Nissman did just that.

In the big peroration at the end of the concerto – clearly modeled after the ending of Tchaikovsky’s Piano Concerto No. 1 – Nissman played with both power and exuberance. There is a lot going on here with tempi and dynamics changing in almost every bar. Conductor and soloist had not quite managed to reach complete consensus; nonetheless, this was joyous music-making.

Ginastera-Nissman Collaboration Has Deep Roots

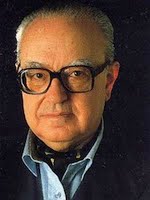

Nissman first met Argentinian composer Alberto Ginastera (photo: right) when she was a student at the University of Michigan. She went on to become one of his foremost interpreters and his Piano Sonata No. 3 Op. 55 is dedicated to her.

Nissman first met Argentinian composer Alberto Ginastera (photo: right) when she was a student at the University of Michigan. She went on to become one of his foremost interpreters and his Piano Sonata No. 3 Op. 55 is dedicated to her.On this occasion Nissman played two of Ginastera’s Danzas Argentinas Op. 2. The first of these is a lovely song with simulated guitar accompaniment and the second, a celebration of the Argentinian gaucho or cowboy in a virtuoso piece bursting with Latin dance rhythms - both great encore pieces - which Nissman played with the utmost panache and authority.

Shostakovich Fifth Symphony Music or Politics?

Scholars still argue over the meaning of the Shostakovich Fifth Symphony - the last work on the program - particularly the final section with its triumphant, major key fanfares. Many, at the time of its writing (1937), took this music at face value, concluding that Shostakovich was forced to compose this kind of ‘programmed propaganda” music under threat from the Soviet authorities.

Shostakovich, since the premiere of his opera Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk in 1934, had been branded as a composer with ‘formalist’ tendencies, meaning that instead of writing music to celebrate the worker’s revolution, he was composing difficult and depressing music.

Before the premiere of the Fifth Symphony, Shostakovich himself had suppressed his Fourth Symphony, one of his most forward-looking and uncompromising works, realizing that if it saw the light of day, he would probably be signing his own death warrant.

Taking into consideration the history of the Fourth Symphony, and the political climate in Stalin’s Soviet Union at the time, the Fifth Symphony is thought to have been an attempt by Shostakovich to win favor by writing music which could be more easily understood by the masses and which left its listeners with a positive message. But there is more to it than that.

This assessment was expounded in Testimony: the Memoirs of Shostakovich (1979), a manuscript compiled by Solomon Volkov, and smuggled out of the Soviet Union. In Volkov’s words:

“I think that it is clear to everyone what happens in the Fifth. The rejoicing is forced, created under a threat, as in Boris Godunov. It’s as if someone were beating you with a stick and saying, ‘ your business is rejoicing, your business is rejoicing, and you rise, shakily and go marching off muttering ‘Our business is rejoicing, our business is rejoicing.’ ”

The veracity of Volkov’s argument is still in dispute in some quarters, but there can be no doubt that in spite of its largely accessible style, the Fifth Symphony is a piece that contains many pages of struggle and despair. The question remains whether all this angst is alleviated in the end in accordance with socialist principles, or something else.

Timeless Power & Beauty: Bay and ASO Get it Right!

Shostakovich composed the Fifth Symphony well over 60 years ago; Stalin is long dead; and since 1989, the Soviet Union has collapsed and been consigned to the dustbin of history.

Most of us today enjoy Shostakovich’s ’s Fifth Symphony purely as music, and are unconcerned about its meaning. One may argue that it is music composed in a context, to be sure, but it endures because of its beauty, its range of feeling and its power to excite us.

My sense was that Peter Bay approached the music in this spirit; that is, pay attention to getting the notes right and the ‘music’ will emerge as the composer intended.

The Austin Symphony performed very well indeed. From the opening bars, the string phrases were precise and played without exaggeration. The dynamic marking here is only forte, after all, and the effect has a distinctly baroque character. The real drama in the piece is yet to come.

Bay followed the composer’s tempo instructions at the beginning of the last movement admirably. Shostakovich was very precise about wanting the movement to start rather slowly, then gradually accelerate over nearly thirty pages of score. It is very difficult for a conductor to make these tempo increases seamless, and the ideal result can only be achieved through sufficient rehearsal and performance.

Whether Peter Bay and the Austin Symphony played the final bars of the symphony as heroic or tragic is for the listener to judge, but there is no doubt that they played them loud. The Dell Hall in the Long Center has admirable clarity, but the players have to dig a little deeper to get enough sound out in the big climaxes. For once, timpanist Tony Edwards got the big sound I have been hoping to hear in this hall.

For Those Wanting More…

Barbara Nissman has recorded all of Ginastera’s piano music (Pierian 0005/6 2CD set) including the encores she played in Austin. She is working on a book about Prokofiev’s piano music and has recorded all nine Prokofiev sonatas (Newport Classic NCD60092/3/4 reissued by Pierian as PIR0007/8/9 3CD set). Bartok enthusiasts might want to check out Nissman’s Bartók and the Piano: a Performer’s View (Scarecrow Press).

While in Austin Nissman gave a Master Class at UT and a recital of works by Bach, Prokofiev, Rachmaninov and Ginastera, in a private home. The highlight of the recital for me was Nissman’s superb rendition of Prokofiev’s rarely-played Piano Sonata No. 6.

For a complete Nissman discography visit her website.

Paul E. Robinson is the author of Herbert von Karajan: the Maestro as Superstar, and Sir Georg Solti: His Life and Music, both available at Amazon.com.

Labels: ASO, Barbara Nissman, classical music blog, Dmitri Shostakovich, Ginastera, Peter Bay, piano