Jacques Lacombe on The Rite of Spring by Réjean Beaucage

/ June 4, 2003

Version française...

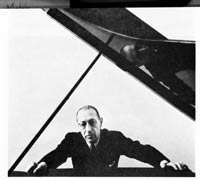

Jacques Lacombe, principal guest

conductor of the Montreal Symphony Orchestra, talks to Réjean

Beaucage

Stravinsky is certainly one of the great geniuses of the twentieth century,

as far as I'm concerned. At the same time, however--and this may seem

shocking--he had a bit of an anti-academic side that goes entirely off the

beaten path. Stravinsky's strength is that he was able to create something

completely new, yet behind the notes you'll find a deeply rooted attachment to

tradition, unlike many avant-garde composers (although it may seem surprising

today to speak of The Rite of Spring as an avant-garde work). In the

early twentieth century there was a romantic current that was on the verge of

becoming outdated. This was the context into which Stravinsky came with a

radically new, anti-academic vision, which nevertheless comprised a very solid

technique and a genius for orchestration. It must have been a magnificent era.

If I had the choice, I'd go back to Vienna at the turn of the century or Paris

at the time of The Rite of Spring. Of course, Stravinsky's work wasn't

always understood at the time, and his music represented a series of hurdles for

musicians. Even today there are difficulties to be overcome when an orchestra

mounts this work for the first time. It's always a stimulating work to do, both

from the standpoint of conducting and technique. There is practically no respite

for the some hundred musicians needed for this work, and they are all called

upon to be virtuosos. Stravinsky is certainly one of the great geniuses of the twentieth century,

as far as I'm concerned. At the same time, however--and this may seem

shocking--he had a bit of an anti-academic side that goes entirely off the

beaten path. Stravinsky's strength is that he was able to create something

completely new, yet behind the notes you'll find a deeply rooted attachment to

tradition, unlike many avant-garde composers (although it may seem surprising

today to speak of The Rite of Spring as an avant-garde work). In the

early twentieth century there was a romantic current that was on the verge of

becoming outdated. This was the context into which Stravinsky came with a

radically new, anti-academic vision, which nevertheless comprised a very solid

technique and a genius for orchestration. It must have been a magnificent era.

If I had the choice, I'd go back to Vienna at the turn of the century or Paris

at the time of The Rite of Spring. Of course, Stravinsky's work wasn't

always understood at the time, and his music represented a series of hurdles for

musicians. Even today there are difficulties to be overcome when an orchestra

mounts this work for the first time. It's always a stimulating work to do, both

from the standpoint of conducting and technique. There is practically no respite

for the some hundred musicians needed for this work, and they are all called

upon to be virtuosos.

The blend of timbres is special

to Stravinsky's music. It forces the musicians to listen to their colleagues

with greater sensitivity. For example, a theme moves from the trumpet to the

oboe or from the English horn to the flute. To find just the right colour to

make the transitions smoothly--because although there are moments when these

must shock the listener, at other times they require a subtle ingenuity--calls

on musicians to exercise great skill and listen carefully to the others. People

are always emphasizing the rhythmic aspect of this music, but once you've really

learned the score, this becomes an added effect, so to speak. Some changes of

tempo seem surprising when you first look at the score, but among the different

sections there are numerous related tempi; once you know the beat you realize it

isn't the tempo that changes but the accentuation. In the "Sacrificial Dance,"

for example, the series of irregular bars is really no picnic to conduct, but

the tempo as such doesn't change. The beat stays the same, and you have to place

the very rapid accents. This is what gives the work its dancing aspect, but you

really have to be sure not to give it a misplaced accent!

It's said that Pierre Boulez amused himself, perhaps as a teaching exercise,

by transcribing The Rite of Spring into 4/4 time. I think, however,

that there's also a psychological aspect to musical notation. Even if it were

possible to find a simpler way of writing the equivalent on paper, the fact

remains that the way music is written determines the message received by

musicians and influences their interpretation. Brahms, for example, often wrote

his music using abnormally long note values. If the basic musical unit is a

quarter-note, a composer writing a 4/4 bar will use four quarter-notes. Brahms

often used half-notes. His symphonies could in fact be rewritten in 4/4 rather

than 4/2 time, but when you're reading the music the half-note gives a sense of

slowness and a wish to sustain the note because it has a long time value.

Stravinsky chose eighth-notes, especially in the "Sacrificial Dance," hence the

impression of a very nervous style in terms of rhythm, and the usefulness of

this notation, which isn't there just to make things difficult.

A beacon

of the repertoire

Igor Stravinsky's Rite of Spring (1913) is of course one of the beacons

of the orchestral repertoire. I think every conductor dreams of doing it one

day. It's one of the first scores I learned when studying at the Vienna Academy

of Music. However, I'll be conducting it for the first time in public this

summer, although I played his version for two pianos when I was at the

Conservatoire de musique du Québec, so I really know it inside out. When we

played it at Vienna it must have been ten years since I'd learned it and I

hadn't looked at it for ages. Nevertheless, when my analysis professor asked me,

as one of the two senior students, to conduct the first part, I did it with

almost no preparation, and everything I'd learned eight or ten years earlier

came back to me very clearly. The same thing happened two weeks ago, when I

rehearsed it with the MSO.

Of course, being asked to appear with the Marie Chouinard Dance Company is a

special situation. I know the choreographer worked with the revised 1947

version, performed by the Cleveland Symphony Orchestra under Pierre Boulez. MSO

musicians are used to playing the original 1913 version. Of course, we'll have

to get closer to the Boulez version to accompany the choreography adequately.

The flexibility which this requires is exactly what defines a great orchestra,

although I should add that Stravinsky's changes to the original score are fairly

minor. Stravinsky used this stratagem several times. Revising his earlier works

enabled him to extend his copyright. This being the case, he didn't make any

crucial alterations. Naturally, because I've been a ballet conductor for a dozen

years I'm used to working with the score on which the choreography is based.

This might seem to be a constraint at first, but it would be just as difficult

for choreographer and orchestra to create the ballet together from scratch. We

need to agree on how each of us will interpret our part of the work in order to

get all parts moving in the same direction. In the present instance, we're

working with a firmly established structure. It's a stimulating challenge to

create my own interpretation of The Rite of Spring on the basis of these parameters,

because when you're working with dance, the nuances between a rapid, more rapid,

or less rapid tempo are very subtle. The difference between fifty and fifty-two

beats to the minute is truly minimal, but the dancers sense it.

There's no doubt that the 'tribal' subject of The Rite of Spring gave

the composer a chance to delve a little deeper in doing his research and to make

this score a bit more provocative than his other works, some of which are more

difficult to listen to. Think of Agon, for example. But The Rite of

Spring remains an incomparable work." [Translated by Jane

Brierley]

The MSO, conducted by Jacques Lacombe, will appear at the Lanaudière

International Music Festival in Joliette, Quebec, on July 26, 8pm, in the

Amphitheatre. On the program: Debussy, Prelude to The Afternoon of a Faun

and Stravinsky, The Rite of Spring, both with the Marie Chouinard

Dance Company. Also: Jacques Hétu, Triple Concerto, Op. 69 for violin, cello and

piano (world première), dedicated to, and performed by, the Hochelaga

Trio.

Version française... |

|