Philippe Herreweghe - Interview by Philip Anson

/ November 1, 1997

Version française...

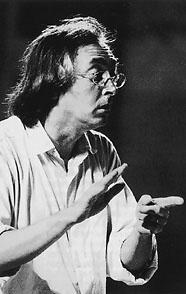

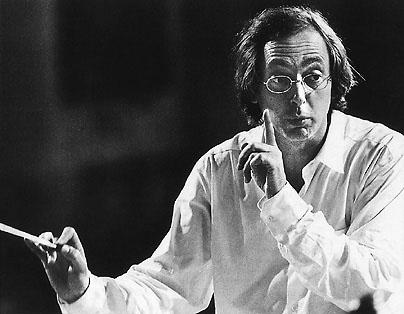

Fifty-year old Flemish conductor Philippe Herreweghe is a

founding father of the baroque authentic practice, original

instrument movement and one of harmonia mundi's most prolific

recording artists, with over sixty albums to his name. His early

training as a chorister and assistant choirmaster in a Jesuit school

was complemented by piano studies at the Ghent Conservatory. At

university Herreweghe studied psychiatry and formed a 12-person

choir devoted to the revolutionary performing practices of Gustav

Leonhardt, Ton Koopman and the Kuijken brothers. In 1970 Herreweghe

gave up medicine, and his choir took the professional name it bears

to the present day, Collegium Vocale. Fifty-year old Flemish conductor Philippe Herreweghe is a

founding father of the baroque authentic practice, original

instrument movement and one of harmonia mundi's most prolific

recording artists, with over sixty albums to his name. His early

training as a chorister and assistant choirmaster in a Jesuit school

was complemented by piano studies at the Ghent Conservatory. At

university Herreweghe studied psychiatry and formed a 12-person

choir devoted to the revolutionary performing practices of Gustav

Leonhardt, Ton Koopman and the Kuijken brothers. In 1970 Herreweghe

gave up medicine, and his choir took the professional name it bears

to the present day, Collegium Vocale.

I spoke with Maestro Herreweghe in October at New York's

Metropolitan Museum of Art before a performance of Mahler's Das

Lied von der Erde with the St. Luke's Chamber Ensemble. As we

sat down in the green room, a stagehand brought Herreweghe a soda

and the Maestro praised New Yorkers for their friendliness. "So

different from Paris", he added with a naughty smile.

SM: Do you come to the United States often ?

-I've been here a couple of times with the Orchestra of St.

Luke's and with my European groups, but touring in America is

financially very difficult, which is a pity because I love the

country.

SM: Have you ever performed in Canada?

-Once, long ago. However, in a few days we are taking the

Mahler to Toronto ... Toronto is in Canada, isn't it?

SM: What is the Herreweghe philosophy on original instruments

and authentic performance?

- The big debate today over authentic performance of

nineteenth-century music such as Beethoven and Schumann on period

instruments is exactly the same as it was twenty years ago about

baroque music. Some of the same critics are even using the same

objections they used back then. At the beginning of the baroque

movement we defended the position that baroque music, for example a

Bach cantata, should be given a chance to be musically convincing in

its original form and on its own merits. First of all, that means

respecting each instrument's fundamental character, le sens même

de l'instrument. One of the problems we encountered was the

disappearance of boys' choirs such as Gustav Leonhardt and I used

for the Bach cantatas on Telefunken. In the old days no one had

cars, so boys went to church on Sunday and learned to sing. Today

families spend the weekend at the beach and there are no more boys'

choirs, so we have to use a mixed choir.

SM: What is the relationship between your many orchestras?

- I give one third of my time to ancient music, one third of

my time to romantic music on period instruments, and one third to

modern orchestras. My groups are like a poupée russe, you

know those Russian dolls that fit one inside the other. My core

baroque instruments group for Bach and German repertoire is

Collegium Vocale. For bigger works and French baroque we enlarge it

to make La Chapelle Royale. For even bigger classical and romantic

works we add about 20 per cent more players to form the Orchestre

des Champs-Elysées. This way I can cover a large repertoire while

maintaining the organic integrity of the groups as much as

possible.

SM: Tell me about your newest group, the Orchestre des

Champs-Elysées?

- The Orchestre des Champs-Elysées was formed in 1991 to

perform nineteenth-century masses, oratorios and symphonic works. We

are a very young ensemble, and due to budget constraints we meet

only six times per year for 2-3 weeks of practice and performance.

The OCE has a stable core of musicians, which is very important to

continuity and quality. Our musicians must be hard-working and

versatile because they play on different members of each

instrumental family for Brahms, Beethoven, Mendelssohn and Berlioz -

back then instruments changed about every thirty years. Many of our

players are professionally interested in organologie. They

collect and some even build their own instruments. Marcel Ponseele,

in my opinion the best baroque oboist in the world, also plays

classical and modern oboe. Of course not every musician can do that,

and I am considering establishing specialized sub-groups within the

OCE for each style and period. Another characteristic of our

musicians is an interest in the history and culture of every musical

period. We play early music together before we play Mozart or

Beethoven. Modern orchestras are often technically brilliant and

emotionally powerful, but they may lack general culture, especially

concerning early music. How can you play Beethoven without knowing

Bach, Handel and Haydn? As I say, to know Venezuela, it helps to

know Spain. The benefit of our authentic approach to the Romantic

repertoire is obvious on our new Schumann recording. Listen to the

balance between the strings and the winds, for example. Because

authentic instruments produce fewer decibels, the winds can blow

fortissimo as Schumann indicated without covering the

strings, something impossible with a modern symphony orchestra.

SM: What is your recording routine?

-Ideally we study and rehearse for five days, then we give a

six-concert tour in Europe. Then we take a break and the next year

study and tour it again. Finally we give two concerts in the same

hall, usually in Montreux, which are recorded. That is how we

prepared all our big oratorios, the Missa Solemnis,

Mendelssohn's Elijah and L'Enfance du Christ. In

November 1997 we'll be recording Schumann's Faust Scenes and

for the first time we will have to use two different halls, which is

a bit worrisome. Normally all the recording would be at the

Concertgebouw, but they can't give us enough time, so we'll do the

main recording in an Amsterdam studio and then the two Concertgebouw

concerts will serve as a reserve.

SM: Do you ever feel you have exhausted the recordable

repertoire?

-Not at all.

With Collegium Vocale I record 2 or 3 albums of Bach cantatas each

year, and there are many more to do. With the Orchestre des

Champs-Elysées, the Chapelle Royale and Collegium Vocale we'll

continue to record Brahms, Schumann and Beethoven. We are also

re-recording Bach's B Minor Mass, and next summer we'll redo

the St. Matthew Passion. I think my early recordings twenty

years ago were fervent in a way that is hard to recapture when you

are older and wiser, but today singers are far better prepared for

period performance, and musicological advances have made us think

differently about the masterpieces. Mahler: Lieder eines fahrenden Gesellen &

Das Lied von der Erde.

St. Luke's Chamber

Ensemble

Dir. Philippe Herreweghe

Metropolitan Museum of Art,

New York.

Opening their North

American tour in the Metropolitan Museum's Grace Rainey Rogers

Auditorium, Flemish early music maestro Philippe Herreweghe led the

fourteen-member St. Luke's Chamber Ensemble in Schoenberg's

bare-bones string orchestra arrangement of Mahler's two great song

cycles. Maestro Herreweghe's authentic instrument interpretations of

Bach, Brahms, and most recently, Schumann are not very different

from Schoenberg's pared-down treatment of Mahler, so Herreweghe was

in his element conducting these hauntingly beautiful scores.

Schoenberg's reduction clears away much orchestral underbrush to

reveal the sturdy trunk and limbs of these austere impressionistic

masterpieces. The real wonder is that a handful of string and wind

instruments fortified by harmonium, piano, celeste and gong, conjure

as much Mahler magic as they do. By reducing secondary symphonic

colors to primary ones the noble, timeless narrative is thrown into

high relief. The result is sometimes ravishingly subtle, frequently

impetuous, but always impressive. The reduced orchestra also means

that the vocal lines are completely exposed. Having suffered through

too many Das Lieds in which the orchestra drowned out the

soloists (I remember how the Met Orchestra at Carnegie Hall swamped

Ben Heppner's not inconsiderable instrument), I was thrilled to hear

the words again. Tenor Thomas Young displayed a rich dark sound and

masterful interpretation. German contralto Annette Markert is a true

lieder singer. Her medium-sized, polished voice brought

memorable vulnerability to her characterizations. Baritone William

Sharp sang the four Lieder eines fahrenden Gesellen with good

German diction in a dramatic manner that somewhat compensated for a

rather average voice. This concert proved that Schoenberg's minimal

Mahler well deserves to become a staple of the chamber ensemble

repertory, as long as the soloists are of the highest quality.

-Philip Anson. The Metropolitan Museum's concert and lecture

series continues through to May 23, 1998. Highlights include

pianists Ruth Laredo, André Watts, Ken Noda, Peter Serkin, Alfred

Brendel (lectures only), András Schiff and André Previn, violinist

Young Uck Kim, the Beaux Arts Trio, Philharmonia Virtuosi, Pomerium,

Quartetto Gelato, Dawn Upshaw and the Aulos Ensemble, Chanticleer,

Anonymous Four, Wolfgang Holzmair and Bo Skovhus. Tel: (212)

650-3949. Fax: (212) 650-2253.

Version française... |

|