Three Great Love Songs by Richard Turp

/ February 1, 2016

Version française...

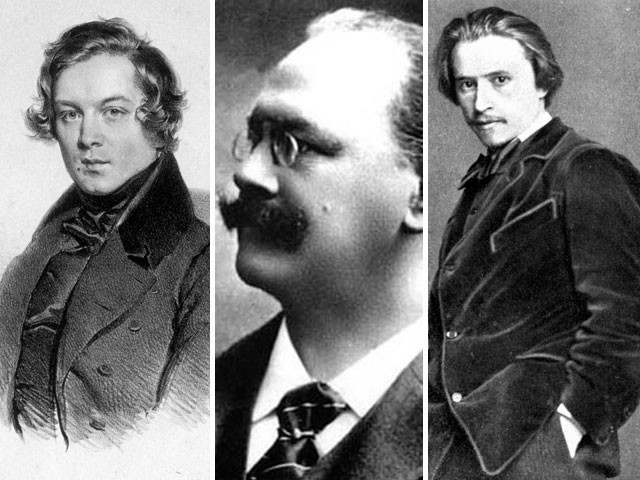

In honour of Saint Valentine’s Day, I offer three great love songs that particularly move me.

Robert Schumann: Du bist wie eine Blume

Robert Schumann’s early and abiding literary influence was Heinrich Heine, the foremost German lyric Romantic poet. Schumann set Heine’s famous poem Du bist wie eine Blume (“You are like a flower”) as part of his opus 25 called Myrthen. Though commonly regarded as a song cycle, Schumann preferred to call it a musical “diary” conceived as an expression of love. He composed it as a wedding gift for his beloved Clara Wieck, and Du bist wie eine blume is the twenty-forth song of the twenty-six that comprise the cycle.

The 1827 poem from Heine’s volume, Buch der Lieder (Book of Songs) has been set approximately 600 times in a variety of languages but none can evoke the reverential and overriding power of love in such apparently simple, concise and moving terms. As musicologist Susan Youens has shown, this poem simultaneously expresses worshipful love and satirizes this kind of sentimental poetry. Schumann not only understood the irony, but deliberately created music that overrides it.

Ultimately what remains is one of Schumann’s most beautiful and fervent songs, which uses nature, and specifically, flower imagery, as a metaphor for his Clara. The song’s repeated chords provide a measured basis for the lyrical declamation of the brief text (the song lasts less than two minutes) with an atmosphere that is one of almost religious, and certainly spiritual, devotion. Its brevity is one of its chief means of emotional impact and demands of the singer not only a poised legato but an unnerving control and simplicity of utterance. In addition, it demands a vocal restraint to perform the ritardandos as slowly and quietly as indicated, as well as an acute sensitivity. There are dozens of fine recordings of the song, but for me two stand out. Canadian baritone Gerald Finley and the superb Julius Drake have recorded a meltingly beautiful version of the lied that is only matched by baritone Wolfgang Holzmair (who produces a heart-stopping subito pianissimo on the climatic schön) and the wondrous Imogen Cooper. Their eloquence reminds us of Heine’s famous phrase, “When words leave off, music begins.”

Henri Duparc: Soupir

Because of a debilitating nervous condition, Henri Duparc left us less than twenty songs, but they number among the greatest creations in the history of French melody. Duparc’s songs are settings of poems by some of the great poets of the nineteenth century such as Baudelaire, Leconte de Lisle, and Théophile Gautier. And indeed though Baudelaire’s L’inivtation au voyage and Lahor’s Chanson triste (which is, ironically, not at all sad) are justly regarded as two of Duparc’s finest “love” songs, my personal favourite is the infinitely moving Soupir, which is a setting of another remarkable “devotional” poem, this one by Sully Prudhomme.

Duparc’s choice of poems is characteristic because musically as well as verbally, his songs are essentially romantic. Duparc’s romanticism, however, is born of a fusion of strength and sensitivity. His musical language often transforms elements of bitterness, sadness and loss, through a modesty of expression and a discretion of accent, into a restorative and healing process and conclusion. Invariably based on a sustained and intense musical line that undulates perpetually, Duparc’s songs gave French melody an impulse, a dimension and a power hardly equalled and certainly not surpassed since. Because of the composer’s rare dramatic sense, they are often of striking expressive quality. This is precisely the case with Soupir.

Like Schumann’s Du bist wie eine blume, it is an apparently simple and short song. The love expressed is no less devotional nor profound but different. Duparc strikes a perfect balance between sensibility and desire, between an exposed and restrained vocal line and an equally diaphanous piano accompaniment. The song is dedicated to his mother and the repeated verses, “Ne jamais la voir ni l’entendre, Ne jamais tout haut la nommer,mais, fidèle, toujours l’attendre, Toujours l’aimer,” (“Never to see her or hear her, never to name her aloud, but faithful ever to wait – and to love always”) express a form of love by means of a musical eloquence rarely, if ever, encountered. The classic version of the song for me is Gerard Souzay’s haunting interpretation, which is particularly memorable for Jacqueline Bonneau’s incomparable playing. A most beautiful modern version is by the Québec duo of baritone Marc Boucher and the prodigiously gifted pianist Olivier Godin.

Hugo Wolf: An die Geliebte

My third selection also has a devotional, reverential feel to it. Between February 16 and May 18, 1888, Hugo Wolf composed 43 settings of poems by Eduard Mörike in a typically remarkable and obsessive release of creative energy. Reading his poems, it is easy to forget that Mörike was a Swabian pastor (more by necessity than choice) for he wrote some of the most subtle, passionate and musical verses in the German language. His range was extraordinarily wide, encompassing ideal, unhappy and erotic love, joy in the natural world, religious mysticism, the supernatural, and broad or ironic humour – all themes richly represented in Wolf’s complete Mörike collection of 53 songs. Wolf and Mörike would have made a temperamentally odd couple but Wolf recognised (well ahead of his time) Mörike’s lyrical genius as a poet. Indeed Wolf’s literary acumen rivalled that of Schumann, and Wolf’s settings of Mörike’s complex quasi-symbolic style and imagery had few, if any, precedents and no rivals. In the best of his Mörike settings, Wolf fused together Wagner’s ineffable evocation of longing with Schumann’s genius for “atmosphere painting.”

An die Geliebte, in von Wolzogen’s words, “carries us up to the heights of hymn and into the depths of mysticism.” It is a song that blends nature, the divine and love. A follower of Wagner, Wolf certainly made uninhibited use of Tristanesque harmonies, and if many of the Mörike songs are harmonically full of Wagnerian sensuality, this song is also essentially lyrical. In An die Geliebte, it is Wolfram rather than Tristan who sings. It opens intimately, as if in prayer, before Wolf’s harmonic language and progressions respond to the text, whether as single words or phrases, leading to a climax of ecstatic sensuality that recedes into a sublime piano resolution. For the singer, the emphasis again is on long legato phrases and a perfect control of dynamics and vocal colour as well as the communication of emotion through words and music. Classic versions by Fischer-Dieskau (with Gerald Moore) and tenor Walter Ludwig bear comparisons with admirable modern interpretations by baritones, Holzmair (with Cooper again), Simon Keenlyside and Malcolm Martineau (live), and especially the vastly underrated Olaf Bär with Geoffrey Parsons. It is proof that Wolf’s songs are, in Ian Bostridge’s words, “about modulating music with words, and vice versa.”

Version française... | |