Jon Vickers by Richard Turp

/ November 1, 2015

Version française...

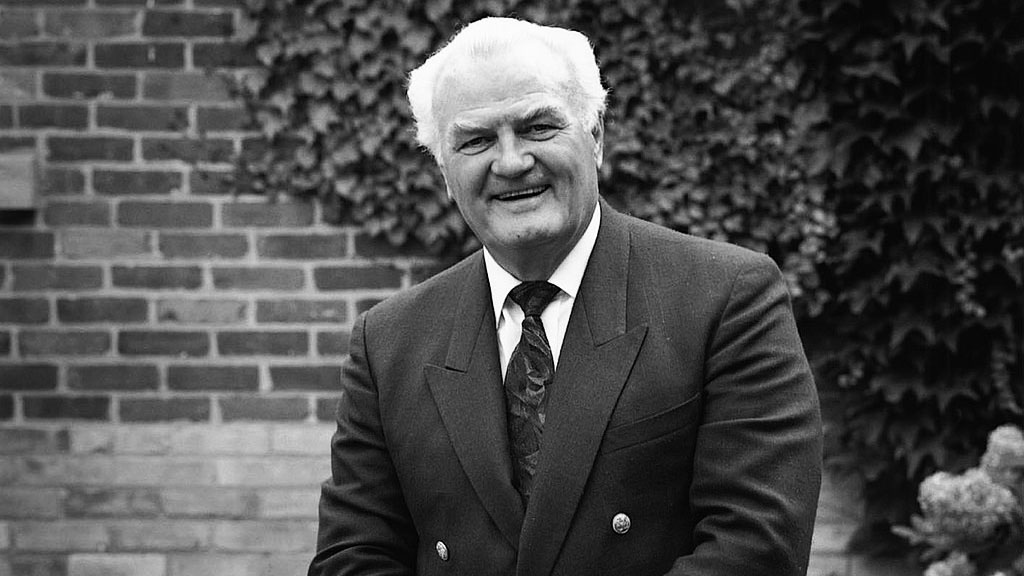

Jon Vickers in 1991. Photo by Harry Palmer

Canadian tenor Jon Vickers passed away at age 88, in July 2015, after a battle with Alzheimer’s. For many, Jon Vickers remains the defining dramatic tenor of his generation. In the dramatic tenor roles that demand the most power and endurance, he had few rivals.

Vickers brought to each operatic incarnation a characterisation that was as personal as his vocal production was unique. Moreover, during his long career of over thirty years, he was often at the centre of controversies, both personal and professional, because he never hesitated to express convictions that many found rigid and inflexible, even shocking.

Born in Prince Albert, Saskatchewan, in 1926, he studied voice part-time and sang at the local church, all while holding a variety of jobs. In 1950, he won a scholarship that allowed him to study at Toronto’s Royal Conservatory of Music with George Lambert. He made what he considered to be his professional debut on stage in 1954, in the role of the Duke of Mantua in Verdi’s Rigoletto at the Toronto Opera Festival (which later became the Canadian Opera Company).

As was the case for many Canadian singers of the era, Vickers was discovered by Sir David Webster, who signed him up for a contract with the prestigious Royal Opera House, Covent Garden in London. In 1957, for his first season, he sang Don José in Bizet’s Carmen, Riccardo in Verdi’s Un Ballo in Maschera, and Aeneas in Berlioz’s epic opera Les Troyens.

London became his artistic base, but he quickly made house debuts with all of the great opera companies of the word, including Bayreuth (1958) and Vienna’s Staatsoper (1959), where he sang the role of Siegmund in Wagner’s Die Walküre. In 1960, he sang for the first time at the Metropolitan Opera – where he subsequently performed around 280 times. The same year marked his debut at Milan’s renowned Teatro alla Scala (Fidelio under Karajan) and at Chicago’s Lyric Opera. Paris and Salzburg followed and his international career evolved at a steady pace until his retirement.

Vocally, Vickers was a young dramatic tenor when he arrived in London. The power and breadth of his voice was both the glory and one of the defining dimensions of his art. The timbre of his voice was instantly recognizable and the voice was graced with a natural resonance, great projection, and impressive depth. Vocally, he was always considered a diamond in the rough. As indicated by a memorable profile, his ample emission was almost muscular and apparently indefatigable, with a voice “marked and scarred as if it came from a Canadian quarry.”

His vocal personality was indeed one of robust power, which, though it communicated emotion, was neither impeccably smooth nor particularly refined. However, his idiosyncratic and unorthodox technique remained intact throughout his career and never ceased to serve his performances well. Vickers knew how to take big risks in performing familiar roles, such as Radamès in Aida. And Vickers was the first to admit that while he took risks giving his all, he risked making his singing less controlled, more unstable, and without great beauty.

Nevertheless, Vickers remained unshakable, incapable of altering the text for a purely vocal effect. This philosophy went back to his very strict Christian upbringing, where hymns and prayers were revered. After he retired from opera, in 1987, he returned to the stage in the 2000s as the narrator of several fascinating presentations of Tennyson’s epic poem Enoch Arden, set to the music of Richard Strauss. According to many critics, the power of his voice remained intact. “He speaks the way he sings,” wrote one critic. “With a mix of delicacy and raw power.”

Vickers identified intensely with the characters he interpreted, especially the misfits and the marginalized, like Peter Grimes, and with psychologically tortured heroes, like Otello in Verdi’s masterpiece or Canio in Leoncavallo’s I Pagliacci. Vickers effectively lent a white-hot intensity to each of his roles. From time to time, the intensity was almost exaggerated and stylistically inappropriate, as was often the case when he ventured into the French repertoire and especially in the roles of Samson and Don José, where Vickers’s performances, as powerful and engaged as they were, where stylistically opposed to the intentions of Saint-Saëns and Bizet. In a quest to identify with each of the characters that he approached, Vickers tended to place himself ahead of the music. This, in addition to his than less idiomatic singing in French, gave rise to what is certainly a conception of the two roles that left a deeply personal but fundamentally flawed conception of both roles.

Vickers had much more success with Handel’s Samson in which, though his vocal and stylistic approach seemed anachronistic to many purists, the spiritual and vocal power as well as the strong character he displayed brushed all possible reserves aside. His portrayal of Handel’s Samson at Covent Garden in 1958 was a searingly dramatic performance. And a generation later, even though his voice coped less easily with the taxing florid line, he was now able to more directly depict the agony of the biblical heroes who, in Vickers’s words, “had lost faith not just in a religious sense, but in the sense that they had betrayed what they stood for.” It was above all Vickers’s capacity to portray moral rectitude with a unique lucidity that was striking.

Here, as in most roles he undertook, much of his histrionic and dramatic conviction resided in his ability (and courage) to sing softly. Vickers’s range, both of colour and dynamics was often breathtaking. During his career, his soft singing was often dismissed as “crooning” or falsetto, but it often was rather an enveloping, fully supported sound, seeming to come from all around the theatre. Here again, some regarded his sudden adoption of a falsetto-like, opaque vocal colour, as a vocal and dramatic mannerism, yet by sheer will and volition, Vickers could entice and ultimately convince in a range of interpretations from Nerone in Monteverdi's L'incoronazione di Poppea at the Paris Opéra to Wagner’s Tristan and Parsifal.

The Dark Side

Vickers was also uncompromising, unforgiving, and unrepentant in his moral rectitude and in his attitude towards homosexuals, and and to what he considered to be the degeneration of western moral values. Many critics accused him of being virulently homophobic, but his defenders insisted that he was simply hostile to what he saw as a real “gay mafia” which, he believed, dominated the world of opera. In the theatre too, Vickers often gave the impression that everyone – the cast, the conductor, even the audience – had to live up to his strict standards. Vickers most famously admonished the audience in Dallas in 1975, when, as the dying Tristan, he turned toward the audience and shouted, “Shut up with your damned coughing!”

There are many authentic stories of Vickers bullying staff at various theatres, and even his colleagues. In 1986, when the Met production of Handel’s dramatic oratorio Samson travelled to Chicago’s Lyric Opera, Vickers insulted conductor Julius Rudel during a rehearsal in front of the entire cast and orchestra, to the point where Rudel offered to quit. However, in interviews, Vickers often spoke of the way that his rural roots and his Presbyterian and Methodist background had shaped his life philosophy:

“The understanding, which slowly and surely developed in me, of the necessity of human contact and an understanding of the needs of others and their problems has probably, more than anything else, given me the ability to analyze my roles, to come to grips with a score, to study a drama, to project my feelings into the life of someone I’ve never met except on a piece of paper.”

In person, Vickers was a sometimes paradoxical being, volatile and enigmatic. He was often warm and charming, and in many ways, decent and understanding, but he could be short-tempered and quick to deride any perceived insult.

In 1961, he crossed swords with conductor Georg Solti at Covent Garden, claiming that Solti had bullied and insulted him during rehearsals for Die Walküre. Then, in 1977, he surprised the opera world with his decision to withdraw from what would have been his role debut in two productions of Tannhäuser at the Met in New York and at Covent Garden, again raising moral questions to justify his decision. Vickers saw Wagner’s opera as blasphemous, calling it “an attempt to strike at the very root of the Christian faith,” and adding that, “Wagner challenged the redemptive work of Jesus Christ.” Certain detractors suggested that it was rather that the vocal range and tessitura of the work had proved too difficult for him.

The controversy that was probably the most revealing with regards to Vickers’s personality was that involving composer Benjamin Britten and his companion, Peter Pears. Pears created the title role of Britten’s Peter Grimes in 1946, and both men considered the theme of the opera to be that of the struggle of the individual against the masses. For many, the opera depicted the persecution of Grimes as a metaphor for the oppression of homosexuals. Vickers clearly rejected such an interpretation. For him, Peter Grimes was a study in “the psychology of human rejection” and his performance followed this idea all the way through, which exasperated and dismayed Britten and Pears. During performances, Vickers’s Grimes would be lost in reverie one moment, then exploding with brutality shortly after. This harrowing portrayal of Grimes, coupled with Vickers’s formidable singing, changed audiences’ perception of the role. When the production travelled to Paris, a critic wrote of Vickers’s performance, saying, “His voice is a long lament, a wail, the cry of a savage beast, a drunken song of beauty and distress that soars above the panicked crowd.”

During an address at the Royal Conservatory of Music in Toronto in 1969, Vickers declared: “I sing because I have to.” Singing, he explained, is “an absolute necessity, fulfilling some kind of emotional and even perhaps physical need in me.”

Vickers always maintained that art should appeal to the intellect as well as the senses, and not just the latter. For him, art involved going well beyond singing. The same spiritual beliefs that led him to be nicknamed “God’s tenor” were at the heart of everything that he did.

As a catalogue of performances now available on CD and DVD amply demonstrate, for more than thirty years Jon Vickers transcended the merely melodramatic and left an indelible mark on every role he performed and on every member of he public who experienced his art.

Translation: Rebecca Anne Clark

Version française... | |