The Herreweghe Legacy by Bill Rankin

/ November 1, 2012

Version française...

Flash version here.

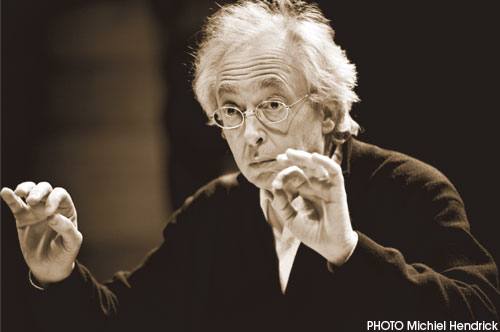

While a student at the University of Ghent, where he was studying medicine in the early 1970s, belgian conductor Philippe Herreweghe created a choir to explore new ways to reveal renaissance and baroque vocal music. This interest in original baroque choral performance practices caught the attention of Nikolaus Harnoncourt and gustav leonhardt, themselves pioneers of historically informed baroque performances, and they invited herreweghe and his choir to contribute to their recording of all of Bach’s cantatas.

There was a disconnect between what period instrument groups were doing and the world of singing when Herreweghe, now 65, began the Collegium Vocale Gent in 1970, says Ivars Taurins, 30-year director of the Tafelmusik Chamber Choir, who as a student, sang in a concert with Herreweghe’s group. “His choir went from strength to strength. It was quite a remarkable sound then, and it still is, different from what I call the utility choir sound,” he explains.

According to Taurins, Herreweghe’s innovations have been rippling through the international choral community for decades. The Belgian multitasker influenced Taurins’s own approach with the Tafelmusik choir. According to Taurins, “Collegium Vocale’s distinctive sound has caught the imagination of many ensembles and conductors. Their sound ideal was my inspiration as a student for what was possible for a choral sound.”

The style itself focuses on a pure, relatively vibrato-less effect; vibrato is enlisted only for ornamentation. This sound is quite common now, but when Herreweghe began, Baroque music was commonly filtered through a more expansive Romantic sensibility.

The Collegium Vocale sound also emphasizes pristine tuning, although notions of tuning are more flexible than you might think. “With the whole idea of ‘singing in tune,’ you have to realize that intonation systems changed over the centuries,” Taurins says. “If you’re listening to the Tallis Scholars singing Renaissance music, and you’re wondering why every chord is glowing, it is because they are aware of this pure intonation system.” Peter Phillips began The Tallis Scholars in 1973.

In recent years, Herreweghe has adapted his choral sound to other repertoire, including works by Baltic and Scandinavian composers. He programs a full range of western music for his instrumental ensembles.

Taurins believes Herreweghe’s musical philosophy embraces a few key ambitions. Besides a devotion to exquisite tuning, the Belgian looks for an unadulterated kind of Bach: “Although passionate isn’t the word I would use, it’s very deeply emotional. There’s a core to his interpretations, especially of Bach, which comes off as something very straightforward and simple, but there’s a lot of thought and heart behind it…The heart of the matter does not lie in the phrasing, the articulation, the intonation, the nomenclature or any other ‘grammatical’ questions to do with the text: it lies in the contents of the works,”

Herreweghe writes in the notes for Collegium Vocale’s latest recording of Bach motets. “It is so easy to become lost in the meanderings of vocal virtuosity, in the aestheticism, gratuitously extravagant rhythms, the ‘playfulness’ or artificial forms of expression… For our part we have sought to respect one and only one line of conduct in our approach: to sing and play the text in a manner of an ‘inspired preacher’ (and a young one at that), who would transmit this text to his parishioners in order to persuade them by moving them — for emotion can but reinforce the power of conviction.”

“Herreweghe’s approach is unshowy and understated, but it’s always very beautifully shaped – an unaffected presentational style,” says Canadian countertenor Matthew White, newly appointed assistant director of Early Music Vancouver, who recorded two series of Bach cantatas and works by Heinrich Schütz with Herreweghe and Collegium Vocale. “It’s very different from the style described as more theatrical or visceral an approach that I associate with someone like Bernard Labadie or John Elliot Gardner,“ he explains. “There’s something very humble about it, especially sacred music. He really shies away from anything approaching histrionics.”

Herreweghe brought an intensified attention to the text in his interpretations. “He’s got an obsession with rhetoric and communicating a text in a certain unaffected way at all times,” White says. “A big part of what he does in rehearsals, which I always found very interesting and useful, is that he would just kind of stare at you and try to determine whether or not at all times you were communicating and embodying the text…If he could see you going the singer mode, where you were just making sounds for the sake of sounding pretty, he would stop you and say, ‘No, no. That’s not what this is about. This is about something deeper than that. You have to connect with the text.’ That’s a big part of Baroque music, understanding the rhetoric and the text. That’s when it becomes authentic and real, somehow.”

Words like “humble” and “authentic” and “true” and “real” come up in conversations about Herreweghe, but according to Christopher Jackson, founder of the Studio de musique ancienne de Montréal, Canada’s oldest Baroque music organization, these notions of authenticity don’t pertain to some of the early music researchers’ obsessions that coloured the early days of the 20th century Baroque revival.

“The word authentic can’t be construed as a kind of curatorial, purist approach to this music, anything but that,” Jackson insists. “[Herreweghe] is much more interested in the substance of the music itself than he is in whether or not you do a trill a certain way or you play an instrument a certain way.”

White agrees with Jackson, who acknowledges Herreweghe’s influence on his own choral practice, but White also appreciates what the early academic investigations into original performance practice gave to subsequent generations of Baroque music performers.

“People say that many of that first generation of folks were overly academic. They spent a lot of time doing academic research that this next generation of early music performers hasn’t had to do,” says White. “The positive thing is there is a whole generation of very talented people, who would have looked at the Birkenstock crowd – as they used to be known – as people who were wasting their time. A lot of the really strong performers recognize that that work was done for a reason.

“So now we’ve got kind of a golden age with all of this academic knowledge that’s helping make the music more expressive, mixed with some really truly international talent. We’ve really got the best of both worlds.”

The authenticity that Herreweghe conveys doesn’t come from some kind of religious zealotry. Bach wrote a lot of his music for the church, and so a performance of the Christmas Oratorio, which unlike the perennial seasonal favourite, Handel’s Messiah, is actually about the birth of Christ, will have a religious cast. But White believes Herreweghe is after more than Christian reverence in his music making. “I feel [he has] a reverence for, not the holiness, but the beauty of the music, and Philippe often gets out of the way. I don’t hear a lot of him; I hear a lot of Bach.

“And that’s something I really appreciate because there’s something about the great 19th-century symphonic conductors that I have a real problem with. I don’t think we need somebody necessarily jumping around and giving us a road map to how we’re supposed to feel,” he explains.

Montreal Bach Festival

Collegium Vocale Gent performs mostly in Europe, although the esteemed Belgian vocal ensemble has toured South America and Asia, and periodically in New York. After more than forty years leading Collegium Vocale, Philippe Herreweghe is bringing his Baroque vocal specialists and accompanying orchestra, 45 performers in all, for performances of Bach’s six-part cantata Weihnachts-Oratorium to Montreal (local debut, Dec. 12 and 13), Toronto (Dec. 14) and New York (Dec. 15.)

Alexandra Scheibler, director and founder of the six-year-old Montreal Bach Festival, says the Collegium Vocale appearance has been several years in the making, and, thanks to financial support Herreweghe’s group gets from the Belgium government, the choir’s mini-tour with stops in Canada was possible.

The MBF always programs with Bach in mind; its concerts include Bach classics, such as the Christmas Oratorio Collegium Vocale is singing at Scheibler’s request, as well as jazz, and even Beethoven and Bruckner. A seemingly remote association with the grandfather of classical music can be enough to justify inclusion, she says, “since Bach is the base of everything that comes after, everything works with Bach.”

Scheibler, a German-trained musicologist who wrote her dissertation on Leonard Bernstein’s sacred music, remembers that when she moved to Montreal in 2005 around Christmas, she did not find a single Christmas Oratorio in the city. That was the main reason she started the Montreal Bach Festival, which runs this year from Dec. 1 to 13.

Messiahs are ubiquitous in North America. In Europe, people listen to Bach’s sacred cantatas, which are actually about Christ’s birth.

The festival gives the vibrant local Baroque scene a stimulus, but Scheibler also invites global all-stars. Akademie für Alte Musik Berlin performed in 2009, and Ton Koopman, MBF honorary patron, has participated several times, including conducting a performance of Bach’s St. John Passion with the OSM last year. Four decades ago, Koopman was doing with instrumental music what Herreweghe tackled in the vocal music realm.

Christopher Jackson says Montrealers give exceptional support to Baroque music. His own group’s first concert 39 years ago drew almost 400 listeners with virtually no publicity.

“Montreal is a bit of an unusual phenomenon in North America. I don’t know if there’s any other city that has 16 early music ensembles. And the quality of the players is so high,” Jackson says. Despite Montreal’s enthusiasm for the Baroque, the city hasn’t been on the A list of high-profile international groups like Collegium Vocale. Jackson praises the Bach festival for luring such artists, “It brings together a lot of the local groups, and it also provides an opportunity to have a more international focus, and we start interacting more.”

bach-academie-montreal.com

performance.rcmusic.ca

Version française... |