Bruce Mather, the Constant Composer by Louise Bail

/ October 1, 2012

Version française...

Flash version here.

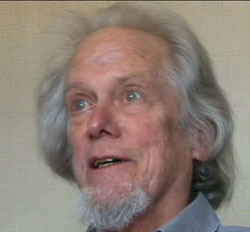

Settled in Montreal since 1966, Bruce Mather, a Toronto native (1939), made his career at McGill University as a professor of composition and analysis (1966-2001). He conducted the McGill Contemporary Music Ensemble (1981-1996), fostering an open and international mindset. Passionate about French culture, he integrated very quickly into the Montreal music scene. He participated in the inauguration of the Société de musique contemporaine du Québec, where he was part of its early boards of directors (1967-1980). The sheer size of his oeuvre shows he was a non-stop worker and a man who cultivated art in every aspect of his life, constantly searching for new ways to explore sound and style. Settled in Montreal since 1966, Bruce Mather, a Toronto native (1939), made his career at McGill University as a professor of composition and analysis (1966-2001). He conducted the McGill Contemporary Music Ensemble (1981-1996), fostering an open and international mindset. Passionate about French culture, he integrated very quickly into the Montreal music scene. He participated in the inauguration of the Société de musique contemporaine du Québec, where he was part of its early boards of directors (1967-1980). The sheer size of his oeuvre shows he was a non-stop worker and a man who cultivated art in every aspect of his life, constantly searching for new ways to explore sound and style.

Mather’s reviewers describe him as being a meticulous and relentless aesthete when it comes to outlining the qualities of good music. Through his opinions of various aspects of the music, its performance and transmission, Mather explicitly delivers his aesthetic position and sense of social engagement through music. Do not ask him to describe what he strives to express through his music; he will tell you that he would do it if he were a poet. As he is not; he claims that he cannot translate into words what music articulates through sound.

However, his music is indeed like poetry. The late Bengt Ambraeus, a friend of the composer, describes an excerpt of Mather’s Music for Organ, Horn and Gongs (1973) as “overlapping, engulfing waves; transitions from one sound to another; a flawless continuity where new structures are born virtually inaudibly...”

This contemplative and meditative nature of his works, which are likened to “illustration[s] sketched around a poetic idea,” is one of the most unique aspects of Mather’s music that the listener will easily recognize in Pommard. His curiosity led him to spontaneously compose the work Pommard for the cello quartet Quatuor Ponticello. Always on the lookout for performers in line with his aesthetic views, he claims to never have written for string quartet, to love the timbre of low strings and especially to have been impressed by the Quatuor Ponticello’s set, which he heard during one of the Ensemble contemporain de Montréal’s 2009 concerts directed by Véronique Lacroix.

In Pommard,the four cellos engage in a whispered dialogue where, in delicate counterpoint, small and large melodic intervals intertwine with each other (fourths and semi-tones against minor sixths) and sixteenth-note rhythms and extended techniques (pizzicati and sul ponticello) glide over one another without stopping more piercing and pronounced fragments from crossing the musical score and asserting the identity of the protagonists, “thereby creating an illusion of distance and proximity.” A fortissimo coda, played over a succession of vast chords, reduces all the parts to a unison, as one would want to preserve the fleeting taste of a good, robust wine...

Pommard displays a great deal of the traits associated with Mather’s oeuvre, including one that secured him a place in the evolution of the composition. The work is written using the quarter-tone system that Mather discovered upon meeting Wyschnegradsky in 1974. Impressed by the theory that divides “the octave into intervals smaller than the semi-tone, ranging from the quarter-tone to the twelfth-tone, these micro-intervals used to create symmetrical subdivisions of non-octaviant space—otherwise put, intervals other than the octave,” Mather found that the system opened up new writing possibilities. He eventually become one of its exemplary masters. Since then, he never stopped composing in microtonality, as Pommard confirms, because the work—to be listened through a microscope—introduces us to the physical world of the infinitely small, a world that can lead to intense and expressive spiritual experiences.

Pommard is also the last vat of “winey” works (there have been around twenty since 1977), as Mather mischievously calls them. Are there comparisons to be made between wine and the work? It is just as difficult to describe wine as it is music, he explains. Some connections can be made, but it doesn’t go much further than that. Pommard is a rich and full-bodied red wine from Burgundy. The experienced oenologist describes the connection between wine and music this way: “A good wine represents a balance between tannin, sweetness and acidity. A good piece of music also represents a balance, between intelligence and the organization of material on the one hand, and expressiveness, emotion and language on the other.”

An eminent and subtle musician, Bruce Mather is undoubtedly a defining figure in Montreal contemporary music. His compositional language, clear but not crude, natural in every dynamic, invites the listener to indulge in the pleasure it arouses. Cultured and on the look-out for meaningful experiences, Mather’s music is like a fine wine.

• Written for the Quatuor Ponticello for its 10th anniversary, Bruce Mather’s first string quartet premiered on May 14, 2012. The work will be performed another ten times throughout the 2012-2013 season. The concert list is on the website:

www.quatuorponticello.com

• Travaux de nuit (for ensemble and baritone), Atelier de musique contemporaine under the direction of

Lorraine Vaillancourt, Salle Claude-Champagne, April 8, 2013

www.musique.umontreal.ca/ensembles

Source: Compositeurs canadiens contemporains. (L. Laplante, dir.). Montreal: Les Presses de l’université du Québec

Translation: Catherine Hine

Version française... |

|