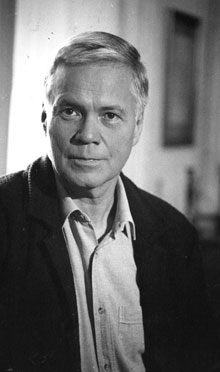

Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau: A Legacy Like No Other by Richard Turp

/ September 1, 2012

Version française...

Flash version here.

It is tough to gauge correctly the legacy Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau has left. On the one hand, it is still too early after his death and his influence is too diverse. One thing is for sure, the more than 500 recordings by the German baritone, who passed away May 18, 2012, were proof that the singer was the most influential of his generation. On the other hand, he is also known as an author and a musicologist, conductor, pedagogue, and in his private life, a painter. It is tough to gauge correctly the legacy Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau has left. On the one hand, it is still too early after his death and his influence is too diverse. One thing is for sure, the more than 500 recordings by the German baritone, who passed away May 18, 2012, were proof that the singer was the most influential of his generation. On the other hand, he is also known as an author and a musicologist, conductor, pedagogue, and in his private life, a painter.

For many, he was not only the last ambassador of classic Germanic culture but also, since the death of his counterpart Elisabeth Schwarzkopf, the gray eminence watching over the German song school.

A talented and precocious artist, (he made his recital “debut” during the war in 1942 at age 17), he established himself at an early age as an extraordinary recitalist. He helped the Liederabend regain its lustre. His colleague Christa Ludwig wrote that “the public went to see Fischer-Dieskau to pray and cry.” He sharpened his versatility after the war in 1947 by beginning his true career in radio as well as in concert and recital on opera stages in Munich and Vienna. Blessed with good looks and an imposing personality, he quickly gained fame for his roles in the works of Mozart (Count Almaviva, Guglielmo, Don Giovanni), Wagner (Wolfram, Amfortas) and Richard Strauss (Mandryka). He fast became a regular on the most celebrated stages: Milan’s La Scala, the Salzburg Festival, the Royal Opera House and New York’s Metropolitan Opera.

Vocally, despite the fact that he lacked an instrument of great beauty or large scale, he possessed a timbre and clarity of diction that were irreproachable. His opera repertoire stretched from G.F. Handel (Giulio Cesare) to Aribert Reimann (Fischer-Dieskau premiered the title role of Reimann’s opera Lear in 1978). His intelligence and musicality allowed him to approach certain Italian operatic roles that require a completely different voice profile than his own (Rigoletto, Macbeth, Falstaff, Posa, etc.), without distinguishing himself however. Similarly, his many forays into the world of French melodie were rarely convincing or idiomatic.

As an icon of German singing, he boasted a voice that was anything but generic. Easily recognizable, it remained homogenous and flexible for more than 40 years–a testament, if there ever was one, to Fischer-Dieskau’s solid self-developed approach. For more than four decades, DFD (as he was called), used his voice with the precision of a surgeon. Particularly, it is the way he used his voice that remains so compelling. In a way, emerging from the chaos of World War II, he was one of the first “modern” singers (maybe even post-modern). His operatic incarnations, his interpretations of lieder and his live performances reflect a more literal approach. The text (musical and poetic) is sacred; the literary and historical contexts fuel and shape the performer. His many available recordings and excerpts on YouTube clearly illustrate that it was principally his consistency, clarity of his vocal and extramusical discourse, and the certainty of his powers as a performer that made Fischer-Dieskau stand out from most of his colleagues.

Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau truly was his country’s son. With a tremendous intellect and a broad culture, he had a meticulous approach and comprehensive care of aspects and of musical and literary levels unimagined in his 400 or so lieder recordings (including integrals of Schubert, Schumann, Wolf and Brahms), of which the most notable were recorded with British pianist Gerald Moore. Equipped with rare depth and uncanny precision, with time Fischer-Dieskau displayed an ultra-intellectual facade, if not mannered and affected.

This is why, as Christian Merlin explains, “it makes sense to think his style is more calculated than spontaneous, more reasoned than emotional.” Fischer-Dieskau is less organic, less “human”, and more perfect than most singers of this generation. In too many instances, his singing did not come from within, but was contrived and hung on a superb framework. Nonetheless, his knowledge and advice made him the most sought-after professor and counselor for any young singer harbouring a passion for lied.

He has become a benchmark for most music lovers and singers alike, and his status as master, dean, and heir of this German culture is tough to uphold for a generation of German singers. It was only after his retirement from the stage in 1992 that a new generation of singers such as Matthias Goerne, Wolfgang Holzmair and especially Christian Gerhaher were able to emerge from his shadow to establish their own artistic identity. To this day, Fischer-Dieskau is still, for some, the measuring stick.

As an author and a musicologist, he has written many works, in particular on the lieder of Schubert, Robert Schumann, Johannes Brahms, Hugo Wolf and poetry by Mörike, Wagner and Nietzsche, Goethe and even the composer Zelter. As a conductor, he directed works by Mahler, Brahms, Strauss, Schumann and Wagner, but, unbeknownst to many, also Tchaikovsky, Verdi (where he conducted his fourth wife, soprano Júlia Várady) and Berlioz. His son Martin followed in his father’s footsteps and became a conductor as well. The former Kitchener-Waterloo Symphony artistic director is now the musical director of the Taipei Symphony Orchestra. Maybe Fischer-Dieskau’s legacy is not so hard to gauge or find an heir to after all...

Translation: John Delva

Version française... |

|