Farid and Godin bring Rachmaninov to life on the keyboard by Emmanuelle Piedboeuf

/ June 1, 2012

Version française...

Flash version here.

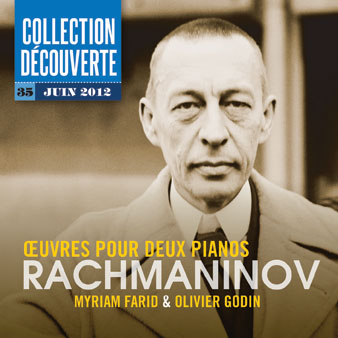

Soon after meeting at the Conservatoire de musique de Montréal, Myriam Farid and Olivier Godin started dreaming of playing Rachmaninov’s difficult Symphonic Dances. Now the duo have accomplished their mission. They have performed the work a few times and, now, their recording is part of this month’s Discovery CD. Soon after meeting at the Conservatoire de musique de Montréal, Myriam Farid and Olivier Godin started dreaming of playing Rachmaninov’s difficult Symphonic Dances. Now the duo have accomplished their mission. They have performed the work a few times and, now, their recording is part of this month’s Discovery CD.

Olivier Godin, well known on the Canadian as well as the international scene, took some time away from his many duties at McGill and the Conservatoire de musique de Montréal to speak with us. The pianist says he enjoys chamber as opposed to solo playing “because being alone at the piano is something incredibly boring” for him. He spent a major part of his career reviving rare French music, mostly with baritone Marc Boucher, and has been a lover of French melodies since his childhood. This Rachmaninov album—”a challenge [he] readily accepted!”—is thus a departure from his usual niche. Godin says he finds what he likes about French music in Rachmaninov: “music from the heart and soul.”

Prelude in C-Sharp Minor, Op. 3, No. 2, the album’s first piece, is one of the works that has followed Rachmaninov his entire life. The prelude, written after the composer completed his studies at the conservatory, quickly garnered attention for its heavy Romanticism, which eventually became its trademark. The prelude’s popularity reached such a point that it became impossible for Rachmaninov to give a concert without playing it. In 1921, he admitted to the Minneapolis Tribune: “I often regret having composed it. (...) I composed much better music that isn’t half as appreciated. (...) It’s as if the public only comes to my concerts only to hear me play this piece.”

Despite Rachmaninov’s frustration towards the prelude, which eclipsed the rest of his repertoire, he wrote a transcription for two pianos in 1938, during the period when he often performed with Horowitz in concert.

When listening to his Suite No. 1, Op. 5 (or Fantaisie-Tableaux for Two Pianos) 40 years later, Rachmaninov said: “Don’t judge this piece too harshly. I wrote it when I was a minor.” However, this suite, based on four poems (by Lermontov, Byron, Tioutchev and Khomyakov), was the work of an accomplished composer. Dedicated to Tchaikovsky, whom Rachmaninov had met at his piano teacher’s home, the piece was astounding not only because of the fluency of its writing but also because of the passages throughout the piece that evoke bells. Additionally, the piano voices’ uniform distribution gives the piece a powerful orchestral timbre, which is recreated in Suite No. 2. Godin points out that Rachmaninov’s language broadened greatly over the years, from a style similar to Liszt to a more modern aesthetic. It is thus normal that, on hearing one of his earlier works, the composer found it outdated, although that need not stop us from finding it worthy of attention.

Composed on a bet, Russian Rhapsody was written in only three days while Rachmaninov was still a student. It was said that writing anything based on a Russian theme was impossible to do, so Rachmaninov jumped at the chance. Choosing a variations form, the composer developed the chosen theme extensively, even alluding to Liszt’s Hungarian Fantasy towards the end of the piece. Alexander Goldenweiser, who was present at the premiere, remembers Russian Rhapsody “ending on a variation in octaves, alternating from one pianist to the next, [in which] each was accelerating the movement.” Rachmaninov simplified the score by removing the accelerando and putting the octaves in the first piano part, resulting in the version we know today.

For Rachmaninov, players could be extremely talented musicians and yet the depth of their music’s emotion and palette of musical colours would never match that of a composer. For Godin, “the role of the performer is not not to do what the composer wanted. It consists in realizing what we profoundly believe the composer wished. (With the work of Rachmaninov), I therefore try to understand this gigantic palette of colours and emotions.”

Godin thinks his work is done if he succeeds at conveying a work’s emotional framework and palette of colours. To transmit this from the score, to the instrument, to the public, is no small feat.

In a not so distant future, Godin will record Poulenc’s entire œuvre of songs to commemorate the fiftieth anniversary of the composer’s death with singers François Leroux, Marc Boucher, Hélène Guillemette, Julie Boulianne, Julie Fuchs, Pascal Gaudin, as well as pianist Billy Eidi. We will also be able to hear Godin in a solo effort playing Chaminaz and in an album of never-released pieces by Ernest Chausson, with Marc Boucher.

Translation: John Delva

Version française... |

|