Flash version here.

Lan Tung inhabits a space of paradox:

as a soloist and collaborator, a performer and composer, she sits at

the crossroads between the East and the West, innovation and tradition.

No wonder she founded an ensemble named Birds of Paradox. That particular

project brings together Indian, Celtic and Chinese musical influences,

but her many other projects—the JUNO-nominated Orchid Ensemble, the

Vancouver Inter-Cultural Orchestra, and Tandava being the main ones—are

no less melting pots of style.

Lan Tung inhabits a space of paradox:

as a soloist and collaborator, a performer and composer, she sits at

the crossroads between the East and the West, innovation and tradition.

No wonder she founded an ensemble named Birds of Paradox. That particular

project brings together Indian, Celtic and Chinese musical influences,

but her many other projects—the JUNO-nominated Orchid Ensemble, the

Vancouver Inter-Cultural Orchestra, and Tandava being the main ones—are

no less melting pots of style.

Taiwanese-born erhu player Tung is

based in Vancouver, but her playing takes her on extensive, diverse

tours. Often, she’s soloing with an orchestra one week and playing

for a visual arts/media or dance performance the next. In between gigs

she studies fiddle-instruments around the globe with players of all

stripes—from the erhu, with principal players in China, Taiwan, Canada

and the U.S. to improvisation with violinist Mary Oliver in Amsterdam,

Hindustani classical music with Kala Ramnath in Bombay, Egyptian music

and maqam with Dr. Alfred Gamil in Cairo, graphic scores and improvisation

with Barry Guy in Switzerland, and vocal music and music therapy, to

boot. Her projects straddle world, new, chamber, orchestral, and multidisciplinary

music. The myriad influences show up in her compositions and improvisations.

This is nothing new, she observes:

the meeting point of cultures “has been an inspiration for musicians

around the world for centuries,” she says. “It’s very natural

that musicians are interested in hearing different styles of music being

mixed together. There may be a clash, a contradiction, but it’s also

where you get the new sounds to come out. I really enjoy playing with

the tension between the differences and the common places.”

If versatility is her calling card

when it comes to musical genres, ironically, it isn’t when it comes

to her instrument. Although Tung studied piano and guitar briefly while

completing her post-secondary degrees, she has rarely strayed from the

erhu since picking it up for the first time at age 10. “I have a collection

of other fiddle instruments from many different countries that I think

maybe I’ll learn to play—but I just haven’t got time to learn

any of it!” she says. “There’s still more to learn with the erhu.”

Yet, learning erhu was no more than a matter of convenience at the time.

“I just wanted to learn any musical instrument,” she explains. “Economically,

Taiwan was still in the beginning of the big rise and so not that many

families could afford a piano, piano lessons. When the Chinese orchestra

[at school] started, it was a chance to learn musical instruments for

free. I joined right away.”

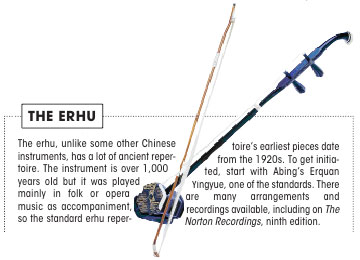

The erhu is commonly described as

a Chinese violin. It’s a useful point of comparison: they’re both

wooden stringed instruments in the soprano voice range—the erhu with

a smaller two and a half octave range—played with a horse-hair strung

bow. But the erhu is held vertically on the player’s lap and the bow

is placed between the two—instead of four—strings. You put rosin

on both sides of the bow and one side plays one string and the other,

the second. The underhand bow hold is more similar to a double bass

German bow hold than the one used for violin—similar to the way you

hold chopsticks. There is no fingerboard: fingers press against the

strings suspended over, instead of on, the wood. All this means the

erhu can be played longer with less fatigue; pitch can be manipulated

not only by moving up and down the fingerboard but also by varying the

pressure on the strings, allowing for a second style of vibrato. Of

course, there are differences between the prototypical erhu instruments

and the standard classical erhu—there are over 50 variations of related

folk instruments from China. The strings were traditionally made of

silk but are now commonly made of steel; Beijing opera instruments were

made of bamboo, southern ones of coconut.

Far from being tired of comparing

the violin with the erhu, Tung believes the interplay between the familiar

and the exotic is what makes intercultural and inter-genre music affecting

and inventive. “When people listen to music, they naturally reference

what they’re familiar with,” she explains. Listening to music “is

very subjective and based on people’s experience. It may not be what

the musicians or composer intends, but that’s fine because that’s

what makes it work. For example, in my compositions I sometimes use

Chinese melodies and then I’ll twist them, make changes to them: the

modes, the notes. That’s really interesting to me because the ear

is used to something and then you create a challenge by having a new

sound. This is why I haven’t got time to learn different instruments!

I’m learning music, not just Chinese music or the erhu. I get to learn

musical languages.”

She pauses, then concludes: “There

is so much more in music if you take away the boundaries between traditional

and contemporary and see only music.”

www.lantungmusic.com

Lan Tung solos on erhu with the

Orchestre Metropolitain in Mark Armanini’s

Heartland:

• January 25, Église Notre-Dame-des-Sept-Douleurs, Verdun

• January 26, Maison symphonique, Montreal

• January 28, Salle Désilets du Cégep Marie-Victorin, Rivière-des-Prairies

www.orchestremetropolitain.com