|

|

|

[INDEX]

Today April 18, 2002, the Montreal Symphony Orchestra accepted the resignation

of long-time Music Director Charles Dutoit which he tendered on April

10. The event leaves all Canadian and Quebec music lovers with mixed feelings.

In his 25 years as Canada’s most famous musical figure, Charles Dutoit

earned the fear and respect of audiences, musicians, politicians, and

journalists. Hundreds of thousands of people heard Dutoit conduct music

live, on radio and on television. Hundreds met him at receptions or glimpsed

him as he rushed between engagements. But despite his eminence and his

central place in the country's musical life, Dutoit was an enigma. Many

knew of him. No one knew him.

Everyone in the music business has had a close call with Charles Dutoit.

Mine came back in 1998 when the Toronto Globe and Mail, Canada’s national

paper of record, asked me to do a major profile of the maestro for its

Arts Section.

I

contacted the MSO press office with an official interview request in September

1998. Weeks passed in silence. When I called back, the Press Office was

evasive: they were considering whether to pass the interview request on.

A month later the administration was still thinking about it. You could

feel the palpable fear and anxiety as Dutoit's underlings tried to handle

this alarming situation. A month after that, someone thought (they were

not sure) that the interview request had been passed to Dutoit. A month

after that, I was told Dutoit would not have time to talk to me. Ever.

So I sat down and wrote a short profile without the maestro’s help. I

contacted the MSO press office with an official interview request in September

1998. Weeks passed in silence. When I called back, the Press Office was

evasive: they were considering whether to pass the interview request on.

A month later the administration was still thinking about it. You could

feel the palpable fear and anxiety as Dutoit's underlings tried to handle

this alarming situation. A month after that, someone thought (they were

not sure) that the interview request had been passed to Dutoit. A month

after that, I was told Dutoit would not have time to talk to me. Ever.

So I sat down and wrote a short profile without the maestro’s help.

My article - “Inimitable, inscrutable Dutoit” - appeared in the Toronto

Globe and Mail on February 6, 1999. My Montreal journalist colleagues

eagerly informed me that Dutoit was furious. The next time I encountered

Dutoit was a few weeks later at one of the regular MSO press conferences.

He was scowling behind his dark glasses and was abrupt with everyone,

as usual. Claude Gingras of La Presse, dean of Quebec music critics, managed

to maneouvre Dutoit and me into a face-off. Out of the blue, Dutoit pulled

off his dark glasses and brandished them at me, snarling, "They’re for

medical reasons!"

Everyone was terrified but I though it was sort of funny. I had remarked

in my Globe article on his Greta Garbo-ish dark glasses. Thats the line

that seemed to bother him most. Poor Dutoit. His hostility and hauteur

concealed a man desperate for respect, love, and understanding. We were

ready to worship him and give him as much great publicity as he wanted.

But he slammed the door in our face. He never made a single human gesture

or had a personal word to spare for anyone I knew in the decades we both

lived in Montreal.

In 1999 I wrote "If there was a secret vote today, [the MSO musicians]

would probably elect him conductor for life." Three years later, the musicians

have voted Dutoit out.

The entire text of my Dutoit profile follows:

“Inimitable, inscrutable Dutoit

February 6, 1999

Toronto Globe and Mail

By Philip Anson

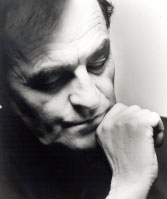

Conductors are today’s classical music stars, better paid and more powerful

than anyone else in the business. They hire and fire, making and breaking

reputations. Canada has no native jet set conductors, but we do have Charles

Dutoit – the aloof and intellectual 63-year old Swiss citizen known as

Charlie to his few musician friends and as Maestro Dutoit to the rest

of us on the rare occasions we get close enough to say hello.

Since taking over artistic direction of the Montreal Symphony Orchestra

(MSO) in 1977, Dutoit has built it into the finest symphony orchestra

in Canada and one of the best in the world. He has made dozens of recordings

with the MSO which have sold over 4 million units world wide. In Montreal,

Dutoit rules over a fiefdom with 123 employees, including 98 musicians,

running on an annual budget of $14 million. Notwithstanding the existence

of a general director, the buck stops with Dutoit and no significant decision

is made without his approval. The MSO has been his show for the last 22

years. He pulls in an annual salary rumoured to be $1 million per year,

which works out to about $10,000 per day for the 100 days per year he

spends in Montreal.

Yet after 22 years on the scene, Dutoit remains a mystery to Montrealers.

In a province where the personal peccadilloes of every public figure fill

the tabloids on a daily basis, Charles Dutoit has remained untouched by

scandal. When in town, he is surrounded by a permanent entourage of MSO

administrators and publicists who run interference and filter every inquiry.

Unlike media-friendly conductors such as Leonard Bernstein, Herbert von

Karajan, Michael Tilson Thomas or Zubin Mehta, Dutoit has shunned publicity

and protects his private life from prying eyes. His schedule is so packed

with rehearsals, auditions, and administrative meetings that the waiting

list for an interview is months or years, and certain topics are off limits.

He terminated a 1997 interview with the Quebec glossy monthly L’Actualite,

in a huff when asked about his reputation as a skirt-chaser. At 63, the

thrice-married Maestro is still a dapper dresser with preternaturally

chestnut brown hair and appetite for the good things in life, the very

image of a continental vieux garcon, a sort of musical Pierre Eliot Trudeau.

Given his aura of power and mystery, when Charles Dutoit makes a public

appearance in Montreal, it is like a royal audience. He ignores everyone,

seems preoccupied, and his rare smiles are ironic. For several years he

has worn sunglasses during press conferences, adding to his Greta Garbo-like

air of inscrutability. But on the rare occasions he opens up, he is a

brilliant talker in several langauges, revealing a deep knowledge of philosophy,

history and politics.

Dutoit has a highly developed sense of his own status. If he demands the

best for his orchestras, it is partly because it reflects on his own reputation.

His $1 million MSO salary - standard for jet-set conductors, but the highest

in the Canadian classical music field - came under fire during the [recent

MSO musicans’] strike from no less a person than Federal Heritage Minister

Sheila Copps. But if the MSO tried to pay Dutoit less, he would probably

leave. Not because he is greedy, but because he knows what he is worth.

He has three major symphony orchestras in his pocket, and they pay him

as much or more than the MSO.

Over the last 22 years Dutoit’s brilliant musicianship has turned the

Montreal Symphony Orchestra into one of the world’s great orchestras.

His administrative savvy has saved the MSO on several occasions, notably

during the recent strike in October [1998] when he was granted several

private tęte ŕ tętes with Premier Lucien Bouchard - celeb to celeb, as

it were - succeeding where the MSO’s general manager had failed. Dutoit’s

unexpected support of the strikers’ demands was a brilliant publicity

coup and earned him the grudging admiration of the 98 MSO musicians.

Grudging because the MSO players do not love Dutoit. Someone once said,

"Show me an orchestra that loves its conductor and I’ll show you a lousy

orchestra." Off the record, the MSO musicians are quick to complain of

Dutoit’s sniffy autocratic attitude, his occasional bad temper, his long

absences, the sense of rushing and confusion on his jet set stopovers

in Montreal. Yet these rebels give their all playing for Dutoit, and if

there was a secret vote today, they’d probably elect him conductor for

life.

To understand Dutoit’s gift, you have only to watch him lead an orchestra.

Animated by the music, his conducting technique is perhaps the most graceful

among living conductors. His gestural vocabulary is elegant, expressive,

energetic yet tasteful, the perfect visual correlative of the music his

orchestra plays. His long thin arms swirl in seamless semaphore movements,

he sways like a willow tree, rising and falling like a cresting wave.

He beats time with his left foot, but the rest of his body language is

balletic, with the lithe grace of a man half his age. When he walks off

the stage he regains his Apollonian composure, but no one would deny they

were lucky to have seen him.

[INDEX]

|

|

|