Shostakovitch's Symphony No. 11: a Soul-searing Mirror of our Troubled Times by Jean-François Rivest and Lucie Renaud

/ March 2, 2003

Version française...

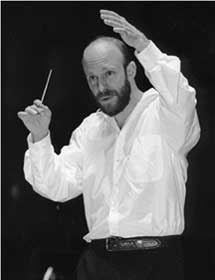

Jean-François Rivest vows an unshakable love for Russian composer Dmitri

Shostakovitch. In the 2002-2003 season alone, he directed the Laval Symphony

Orchestra in Shostakovitch's Symphony No. 5, then made the arrangements

and directed the Ottawa Thirteen Strings in a revisited version of the Third

Quartet. On April 4, he will lead his students from the University of Montreal

orchestra in a performance of the Symphony No. 11. The maestro explains what

thrills him about the composer and presents his vision of the

masterpiece. Jean-François Rivest vows an unshakable love for Russian composer Dmitri

Shostakovitch. In the 2002-2003 season alone, he directed the Laval Symphony

Orchestra in Shostakovitch's Symphony No. 5, then made the arrangements

and directed the Ottawa Thirteen Strings in a revisited version of the Third

Quartet. On April 4, he will lead his students from the University of Montreal

orchestra in a performance of the Symphony No. 11. The maestro explains what

thrills him about the composer and presents his vision of the

masterpiece.

I regularly program

Shostakovitch's works because I believe that he is a major composer. I have

developed a personal liking for him. I think that I am really not a very serious

person in everyday life (Rivest is particularly fond of the caustic humour of

François Pérusse), but I love serious music. I believe that too often we tend to

analyze music with a magnifying glass and view it as an object of knowledge.

Shostakovitch, on the contrary, remains in direct contact with our

emotions.

Shostakovitch commands special

attention from the public. One music lover wrote that his works crave for a

public. Even though the composer strives to convey faithfully the image of one

nation, he depicts the woes of all nations, using the disasters and cataclysms

survived by the Russian people. In his music he guides us to an intimate

understanding of other people's day-to-day lives.

I strongly believe that music is

the best medium for empathy. I am convinced that we absolutely need empathy to

play music, empathy towards the public, the composer, and the musicians with

whom we play. This empathy allows the listener or the interpreter to feel the

emotions experienced by others, even without having lived through them

personally.

The Symphony No. 5, probably Shostakovitch's most famous work, remains

fundamentally classical: first movement in sonata form, slow movement, scherzo,

and finale. Underneath appearances, it was composed with an ultra-modern

language and in this it succeeds (I mention it to allow you to understand the

Eleventh). It creates a channel that

may be perceived by certain party members as glorifying the recent USSR and its

army (there are several military marches), but in which I believe the population

recognizes its hatred for military power, oppression, and humiliation. Music is

transformed into an outcry for survival, the raw side of life.

The multiple facets of Shostakovitch's work fascinate me as well the power

imbedded in his music, but I don't mean the surface-level power of cymbals and

trumpets. I would compare it to a hologram. Behind a very simple and repetitive

writing composed primarily of quarter and eighth notes, with mostly a classical

structure and sometimes simplistic themes (the Eleventh presents popular

songs of the Russian Revolution), it hides an incredibly structured mind which

holds all parts together as efficiently as a Beethoven symphony, albeit in a

more rocky, crystalline, earthly, sharp, metallic, and compact way.

From Beethoven's Eroica onwards, symphonies have been the mirror of an

entire world thought out by the composer, the zenith being achieved,

indisputably, in Bruckner's Fifth, Brahms's Second, or Mahler's

Ninth.

Shostakovitch doesn't fall into this category since communication is the driving

power behind his work. He always sets the social context in troubled times,

refusing to create a comfortable world for us; his prime goal is to tell us the

hardship of his nation. It is not the listener who travels, but Russia which

enters into us, aggressively. Thus we owe it to him, on the grounds of human

solidarity alone, to feel these emotions.

Although Symphony No. 11 describes the violent events of January

9, 1905, it reflects deep down any uprising against oppression, at any moment in

history. Starving peasants march on the St. Petersburg winter palace. The first

movement portrays the underlying tension preceding this event: a slow orchestral

prelude, but enveloped in a cold ambiance, extreme tension, with the strings

straining at discordant chords, trumpets sounding as if preparing for battle,

timpani beating erratically. We hear songs of the Revolution from a far

distance, very softly and slowly. Almost slyly the second movement starts. Then

abruptly the crowd gathers, pushes, the guards push them away, and suddenly the

unbelievable occurs: Russians shoot Russians, brothers kill brothers, hundreds

lie on the snow in their blood, a vision from hell. The mass hysteria is

brilliantly depicted in one of the most horrifying musical narratives known to

me, a traumatic experience. The third movement is a gigantic funeral march,

rendered in a near-obscene way by its pizzicati, almost dodecaphonic, from which

emerges a sublime melody played by the viola. The last movement is ambiguous, as

if war were starting again, as if the dead were calling for revenge. Did

revolution win or did humans succeed in going beyond their pain? We will never

know, as Shostakovitch purposefully maintains his ambiguity.

Technically speaking, the symphony remains very difficult to play, and it is

my duty as a conductor to bring out the best in each musician. The music

requires close cooperation between musicians, so that they become one with the

subject and also have the desire to communicate these emotions. An intent

has to be conveyed; this work cannot be treated as an object of beauty to be

appreciated. Emotions must be communicated uncompromisingly. The Elventh is more powerful than [Shostakovitch's]

preceding musical works, it touches everybody, within the orchestra as well as

in the concert hall. The [UdeM] students loved it from the first reading. They

talked about it, and some violinists no longer in the orchestra even wanted to

rejoin it for this concert. This music shakes your inner soul, haunts you all

the way into your dreams.

The maestro's recommendations

Jean-François Rivest recommends three recordings of the Symphony No.

11. Two are historical readings, one by the Moscow Orchestra conducted by

Kyril Kondrashin and the other by the Leningrad Symphony Orchestra under Evgeny

Mravinsky. There is also a new version by the London Symphony Orchestra

conducted by Mstislav Rostropovitch which Rivest terms "astonishing".

[Translated by Caroline Labonne]

April 4, salle Claude-Champagne, Montreal, (514)

343-6427

Version française... |

|