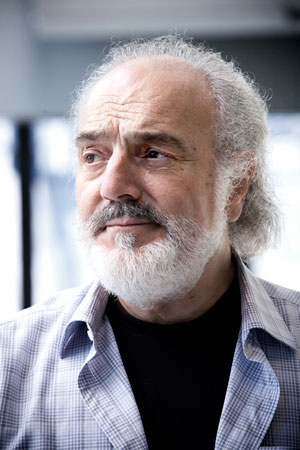

John Rea: The Butterfly Man by Réjean Beaucage

/ September 1, 2015

Version française...

Composer John Rea will be the star of Société de musique contemporaine du Québec’s Homage Series for its 2015-2016 season. He follows in the footsteps of Claude Vivier, Gilles Tremblay, Ana Sokolović, and Denis Gougeon, and like them will prove there’s plenty to pack into one season. Composer John Rea will be the star of Société de musique contemporaine du Québec’s Homage Series for its 2015-2016 season. He follows in the footsteps of Claude Vivier, Gilles Tremblay, Ana Sokolović, and Denis Gougeon, and like them will prove there’s plenty to pack into one season.

“Friedrich Nietzsche said that without music, life would be a mistake. My father loved music, and he played it too. I know, for example, that when he was young, living in Italy, he played in the village brass band. And music was part of my youth as well. I learned to play the piano, and my father encouraged me to begin composing. He respected what I did, but couldn’t judge the quality of my work. For that, he waited for some kind of external approval, which came when I began to win prizes. In 1969, I got a prize in Switzerland for an orchestral work [third prize at the International Competition for Ballet Composition with The Days/Les Jours]. My father was able to appreciate the work when it was finally performed [by the Toronto Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Marius Constant] in 1974,” says Rea.

Born in Toronto in 1944, John Rea moved to Detroit at the age of eight. He graduated in 1967 from Wayne State University, Detroit, with a bachelor’s degree in piano and composition. He returned to Canada to obtain a master’s in composition from the University of Toronto in 1969, and then went to Princeton, where he earned a PhD in composition and music theory in 1978.

He was back in Toronto in 1973, to attend the premiere of his chamber opera for children, The Prisoners Play, before finally moving to Montreal the same year.

“That opera was part of my doctoral thesis, and it was performed for the first time in May that year. A week earlier or later, I was interviewed for a job at McGill,” he explains.

He adds, laughing, “Quite the start for what might be called a life ... of theory!”

Alongside that season’s busy activities and concerts, John Rea continued to teach composition at McGill University, as he has done since 1973.

“Teaching was a great revelation for me,” he says. “I soon realized that I’m the first student! I learn a lot from talking with students and gain a better understanding of how to teach. It’s not so much the professor conveying the subject matter as the students discovering it for themselves. I have amazing doctoral candidates and I love the energy of teaching, so I think I’ll keep at it for a while!”

Forging ahead

John Rea’s involvement in the Montreal music scene is far from theoretical. He rapidly became one of the pillars of the musical community with his work at McGill, of course, but also via his efforts to push the discipline forward. In 1978, along with José Evangelista, Lorraine Vaillancourt and Claude Vivier, he was a founding member of the new music society Les Événements du neuf.

“Our aim was to decompartmentalize contemporary music,” he explains, “following the fashion of the time.”

It was thanks to his McGill colleague Alcides Lanza that Rea met the composer José Evangelista, with whom he was to found the organization Traditions musicales du monde (TMM).

“Evangelista taught me another way of approaching music, and he got me to develop the receptiveness I already had towards music from other cultures,” he clarifies. “For a while, I explored Indian music — like many other young people in the sixties, I suppose. TMM was great fun because of intergovernmental partnerships that made it easy to invite artists from practically everywhere, and we had at least five concert seasons.”

In 1982, Rea also joined the SMCQ’s Artistic Committee, with whom he would stay for over 25 years.

It’s not surprising that Rea also enjoys writing about music, and a few years later he joined the editorial committee of the music review Circuit : musiques contemporaines, cofounded in 1989 by Lorraine Vaillancourt and Jean-Jacques Nattiez. He was an active participant there until 2011. The first issue of the journal was devoted to postmodernism, a term often used in connection with Rea’s music.

He reminisces, “This takes me back to my friend and colleague José Evangelista and a recording project produced by the Canadian Music Centre. It was an album of works by Denis Gougeon, Claude Vivier, Evangelista, and me [Treppenmusik], and we were looking for a title. It was Evangelista who suggested ‘Montréal postmoderne’. When the record came out [in 1984], there was much discussion about the use of the term. Some people were angry even, because of the pejorative connotations of the word, as if we were making fun of our illustrious predecessors. The debate went on for at least five years and is one of the reasons why Circuit made it the subject of its inaugural issue. I also gave a lecture on it a few years later [“Postmodernit́é ‘que me veux-tu’”, given in May 1995 at the Chapelle historique du Bon-Pasteur; text published in Circuit: musiques contemporaines 8, no. 1, 1997].”

The term seems to cling to John Rea perhaps because of the success of pieces by other composers that he has revisited, like Claude Vivier’s Pulau Dewata, orchestrated in 1986, or his reorchestration of Alban Berg’s opera Wozzeck, which became very successful after its premiere by the Nouvel Ensemble Moderne (NEM) in 1995.

“Postmodernism in music certainly has a tendency to look back, and I’m thinking of Luciano Berio and his Folk Songs [1964] ... They’re magnificent works, but I’m inclined to wonder what someone like Boulez thought of them at the time. Postmodernism was a sort of betrayal for the high priests of modernity. So at the time, Berio could be seen either as a traitor ... or a new prophet! A pleasing paradox. To modernists, the arrow of time flies in one direction: straight. But celestial mechanics shows us that there are epicycles, and reversals that allow us to continue on our way,” he says.

Revisiting the past

If the SMCQ’s Homage Series constitutes a look back for the composer as he considers his work so far, one can imagine it will give him a strong impetus for the future.

“It’s very seldom a composer has this opportunity,” he admits, “even if you consider what’s happening elsewhere in the world. A whole year — more, actually, because you have to prepare for that year! You spend at least 18 months observing how other people view your music. There’s a whole team working on the project, totally dedicated to this cultural activity. Normally, in-depth studies like this are reserved for ... dead composers! So I’m very grateful to the organizers of the Homage Series, as I’m sure my predecessors were. I should also stress the educational aspect of the series, because the recipient of the tribute has to compose a piece to be played by primary and secondary school students. It’s harder to write for the younger ones, as you have to bear in mind their limits as players. But I absolutely love it. I was asked to draw on one of my own works, Médiator ( ... pincer la musique aujourd’hui ... ) [1981], so I wrote a piece on plucking, but it will be played on flutes, xylophones, etc.”

John Rea will have a further opportunity to revisit his work when the Ensemble de la SMCQ plays a big band version of his piece Big Apple Jam, originally written for saxophone quartet.

“It’s very funny, because the original project, with a band, was intended to simulate a big band, but Walter [Boudreau] suggested I do it for real,” he explains.

As for new works, some will be performed next May at the Maison symphonique de Montréal.

“I wrote some pieces for the Grand Orgue Pierre-Béique, an outstanding instrument. It’ll be an evening of music and dance, with Le Carré des Lombes, choreographer Danièle Desnoyers’s company. I’ve also written a piece for the NEM, to premiere around the same time. Lorraine Vaillancourt is planning to collaborate on it with the vocal ensemble Soli-Tutti, from France,” he adds.

The NEM also graces the opening night on September 25, playing works by Pierre Boulez (Éclat/Multiples), John Rea (Accident [Tombeau de Grisey]) and Alban Berg. Rea reorchestrated Berg’s Three Pieces for Orchestra at the joint request of the Winterthur Musikkollegium in Switzerland and the NEM, which premiered the work with great success at Winterthur last March.

“It’ll be quite an event,” says Rea, “because there’ll be two concerts. There’s the NEM one at 8:30 at the Maison symphonique, but before that, at 7, the SMCQ will launch the evening at salle Pierre-Mercure with a concert in tribute to the last composer to receive the Homage, Denis Gougeon. It will feature his work Clere Vénus, and Walter Boudreau will also conduct my piece Man/Butterfly [the full title of which is: I do not know whether I was then a man dreaming I was a butterfly, or whether I am now a butterfly dreaming I am a man]. Also, there will be the first performance of a piano concerto by Silvio Palmieri. A packed evening!”

That opening night will be the start of a long process from which John Rea might well emerge ... transformed.

Translation: Cecilia Grayson

· Éclat/Multiples, Nouvel Ensemble Moderne, Accident (Tombeau de Grisey) by John Rea, and Trois pièces pour orchestre, Opus 6, orchestration by Rea. September 25 2015, 8:30, Maison symphonique. www.lenem.ca

· The Butterfly Man, SMCQ, Homme/Papillon by Jon Rea. Le Septeber 25 2015, 7pm, salle Pierre-Mercure, Centre Pierre-Péladeau www.smcq.qc.ca

Version française... | |