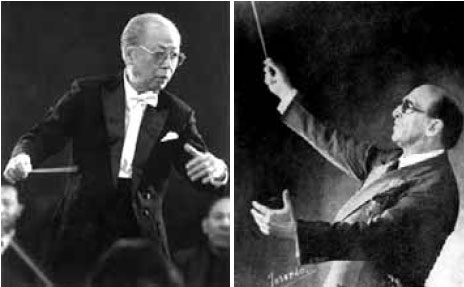

Huang Feili: The Father of Chinese Conductors by Paul E. Robinson

/ June 1, 2012

Flash version here

In March of 2009, I was at the Central Conservatory in Beijing giving a lecture on Stokowski to a class of young conductors. But just before my talk was to begin I had a surprise visitor: 92-year-old Huang Feili, the man who had founded the conducting department of the Central Conservatory back in 1956. Given Mr. Huang’s great age and distinction, his presence did me a great honour. But in addition, I was overjoyed to see an old friend whom I had first met in Toronto in 1987.

The history of Western music in China has been well told in a recent book called Rhapsody in Red. But what is particularly fascinating to me is the struggle faced by Chinese conductors to find opportunities for training and growth, and ultimately to become masters in their own house. At the very centre of that struggle was my old friend Huang Feili.

The story really begins in Shanghai with the arrival of the pianist-conductor Mario Paci in 1918. Paci was born in Florence and had developed a flourishing career as a touring virtuoso. He hadn’t planned on staying in Shanghai but illness confined him there for several months. One thing led to another and before long he was conductor of the Shanghai Municipal Orchestra. This orchestra could trace its roots back to 1879 when it was little more than a small band, but it became an important cultural asset among the foreigners living in the International Settlement. Mario Paci reorganized and reinvigorated the orchestra from 1919 until 1942 when war with Japan ruined everything.

The quality of the Shanghai Municipal Orchestra should not be underestimated. Among its members was Walter Joachim, who was principal cello for eleven years. After settling in Canada in 1952, he became principal cello of the Montreal Symphony. There is no doubt that for more than 30 years the Shanghai Municipal Orchestra was the finest symphony orchestra in the Far East.

As a young man, Huang regularly attended Paci’s rehearsals. Huang never had formal training in conducting. As he puts it, “My conducting was ‘stolen’, mostly from Paci!” Interestingly, given my reason for being in Beijing in 2009, Huang also recalls another important influence on his conducting education in the 1930s: Stokowski’s 1937 film with Deana Durbin One Hundred Men and a Girl. Musical life in Shanghai in those days was surprisingly rich with performances by artists of the stature of Heifetz, Szigeti, Elman, Moiseiwitsch and Chaliapin.

After the war, Huang Feili was able to broaden his experience by going to study music at Yale University with, among others, Paul Hindemith. By this time Huang played the violin well enough to join the New Haven Symphony and work with soloists like Serkin and Primrose. There were also opportunities to see Koussevitzky, Monteux, Stokowski, Mitropoulos and others at work in nearby Boston and New York.

When he graduated from Yale in 1951 Huang returned to China and joined the Department of Composition at the Central Conservatory (CCM). Among his other assignments he taught conducting. One of his early successes was a production of Tchaikovsky’s Eugene Onegin with students of the CCM. Huang was the conductor and it was an historic occasion: the first performance of a Western opera in China featuring Chinese singers and musicians.

By 1956 Huang had had such an impact on the CCM, the musical life of Beijing and nearby Tianjin that he was asked to start a Department of Conducting. His dream was to create, as he put it, “a Chinese School of Conducting.” What he had in mind was an approach to conducting that was uniquely Chinese. The “school of conducting” was analogous to the schools that existed in other art forms in China such as the Peking Opera and its various “schools” which each feature unique singing and acting.

But with time and experience, Huang came to realize that his dream was “impractical, impossible and even unnecessary.” Even the “immutable” schools of the Peking Opera have changed, and living in a global village as we are today, Huang finally understood that change is probably inevitable and healthy.

Huang Feili not only became a respected teacher at the CCM but also one of the most prominent conductors in China. In the mid-1970s, he was invited to head up a student ensemble that later became one of the finest professional orchestras in China: the Beijing Symphony.

Huang Feili is now 94 years old and lives in Beijing. Every Saturday, he still conducts a rehearsal of the 80-voice Beijing Yuying Beimang Alumni choir. This ensemble combines alumni from two schools founded by the American Congregational Church: Yuying (boys) and Beimang (girls) high schools.

If Huang was not able to create a uniquely Chinese school of conducting, what he did help to nurture was several generations of Chinese conductors trained well enough to take over their own orchestras. A foreigner like Mario Paci got things started many years ago, but the present and the future are in the hands of excellent homegrown musicians. |